The Abrams House is a bright, playful postmodern house hidden in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, a city better known for vinyl-sided row houses, simple two-and-a-half story brick homes, the occasional Gilded Age mansion and the many Gothic Revival monuments throughout its older neighborhoods. Although the Abrams House is unlike anything else in the city, it emerged organically from its surroundings, brought to life by a woman who took inspiration from several daring efforts nearby.

The one-and-a-half-story house is relatively unknown even to those who avidly wander the city, searching out its built charms. It sits on the private Woodland Road, on the back half of a lot, making it hard to spot without trespassing. To come upon the house at the end of its slightly curved driveway is surprising, like a sunrise through the trees: a pale starburst radiates from the front door, a jagged edge marks its undulating roofline.

A Path to Postmodern: The Abrams House, a Pittsburgh Legacy

Author

Eric Lidji

Affiliation

Director, Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives at the Senator John Heinz History Center

Tags

Betty and Irving Abrams commissioned the house in the late 1970s as a place to spend their final years. They had been inspired by four decades in close proximity of some of the most ambitious residential architecture in the city, starting with construction of the Frank House. A cousin through marriage, Robert Frank had commissioned Walter Gropius and his partner Marcel Breuer to design the four-story house on Woodland Road in 1939. The reputation of the house has grown over the years, so that now it “may be the largest, most complex, and most luxurious Modernist house of its time,” as former Carnegie Mellon University architectural librarian and archivist Martin Aurand described it. The house survives largely in its original state and by Alan I. W. Frank.

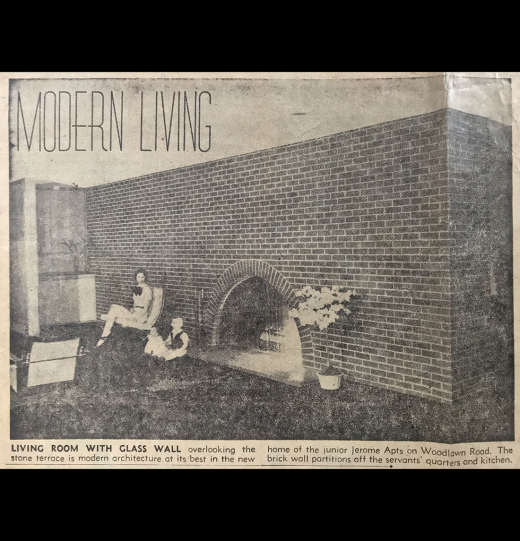

A decade later, in the early 1950s, Robert Frank’s daughter Joan Apt invited architect A. James Speyer to design her and her husband Jerome’s house, also along Woodland Road. Speyer came from an old Jewish family in Pittsburgh but had relocated to Chicago to train under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, where he absorbed his mentor’s minimalist principles. He is believed to have introduced Robert Frank to Gropius and Breuer. The Apt House is modern, open and elegant, with a wall of glass looking onto a secluded landscape. Apt lived in the house until her death in February 2020, when it was sold to new owners.

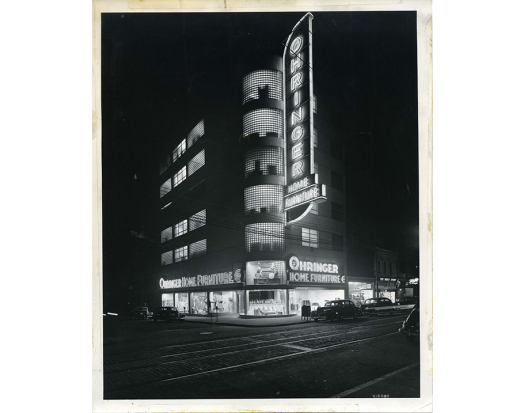

Betty Abrams was one of four children of Abe and Helen Ohringer, who had immigrated to the mill town of Braddock, Pa. in the early 20th century from Eastern Europe. The Ohringers ran a successful furniture store in Braddock with branches in several neighboring small towns. As the operation grew, the Ohringers built an eight-story headquarters along the main street of Braddock in 1941, designed in the Moderne style with a curved front of large glass block windows. It was the most architecturally current building in the small mill town. It is currently being .

The influence of Jewish designers, architects and patrons on midcentury modern architecture and home design in America is well documented, particularly through the 2014 exhibit and catalog “Designing Home: Jews and Midcentury Modernism,” first held at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. The trend found its way to Western Pennsylvania as well, most famously when the Kaufmann family commissioned Fallingwater from Frank Lloyd Wright in 1937. Wright’s students, Cornelia Brierly and Peter Berndtson started a private practice in Pittsburgh, designing at least eight notable modern homes in the eastern neighborhoods and southern suburbs of the city through the mid-1950s. Several of these homes were for Jewish clients, including the Edward Weinberger House (1948) and the Abraam Steinberg House (1951-52), both in Squirrel Hill.

Those projects coincided with an urban renewal movement known in Pittsburgh as Renaissance I. The effort ushered large-scale modern architecture into the city through projects like Mellon Square, the Civic Arena, and Point State Park. In the decades since, the aesthetic legacy of Renaissance I has been overshadowed by the leading role it played in the destruction of several Black neighborhoods and the relocation of those residents.

A second wave of urban renewal in the 1980s, called Renaissance II, began with the announcement of five new downtown skyscrapers, including a glass neo-gothic castle for PPG Industries designed by Philip Johnson and his partner John Burgee. Those years also saw the arrival of postmodern residential and civic architecture throughout Pittsburgh, particularly in the work of two local architects, Arthur Lubetz and Tasso Katselas.

The Abrams House reflects both eras of renewal. It was commissioned by children of Renaissance I and designed in the spirit leading up to Renaissance II.

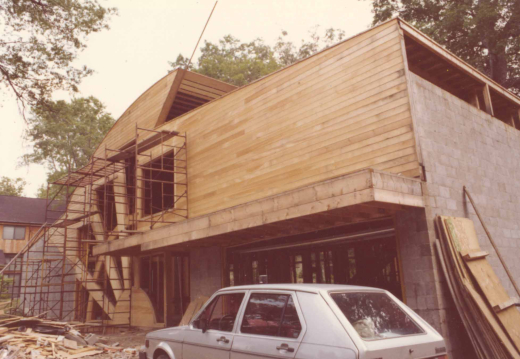

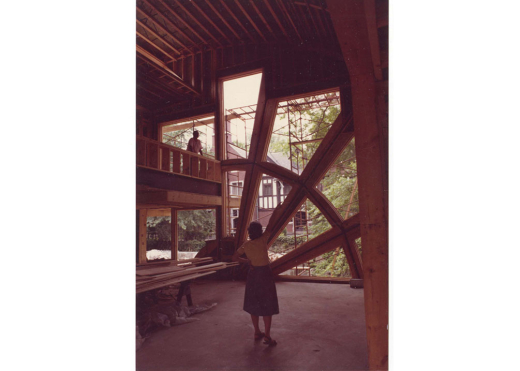

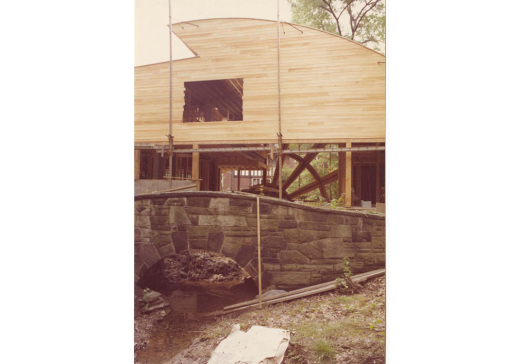

After meeting with several leading national architects including Michael Graves, the Abrams hired Venturi, Rauch & Scott Brown. Robert Venturi seems to have been inspired in his design by an old stone bridge left at the back of the small lot. The house mimics the curve and the scale of the bridge, but it adds a jagged angle to the roofline and the glow of pinwheel windows radiating into a starburst design across the wood-paneled façade. Construction finished in 1982. The Abrams gradually furnished the house with aesthetically appropriate décor and art, including Memphis Group furniture and a wall-sized print by Roy Lichtenstein, as well as smaller works by Warhol and others.

Following the death of Betty Abrams, her family sold the house to the current owners of the Giovannitti House, located on the front half of the lot. Frank Giovannitti and his wife, Colleen Hess financed the project in the late 1970s by subdividing and selling parts of their property. They hired Richard Meier to design a white and light-filled geometric house based on a deconstructed cube, completed in 1983.

The current owners of both innovative homes conducted extensive internal demolition of the Abrams House and later secured a demolition permit. The house was still standing as of early 2021 and the matter remains unresolved, however, the activity set off a preservation debate in a city not accustomed to having such conversations about buildings less than 50 years old.

Sources

Abrams Family Papers, Rauh Jewish Archives at the Heinz History Center

“,” Martin Aurand

“,” Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation

About the Author

Eric Lidji is the director of the Rauh Jewish Archives at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In Between Rivers: Pittsburgh's Modern Milieu is part of the °®¶¹app Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, Michigan, Houston, , , and Kansas. Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting °®¶¹app or so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.