Pittsburgh's Modern Milieu Part Three

Hidden in Plain Sight: Kiley’s Sarah Scaife Gallery Landscape

Dan Kiley’s exceptional landscape for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s Carnegie Museum of Art’s Sarah Scaife Gallery is compromised but not forgotten. The city’s design and preservation community, and the leadership of the museum, have within their grasp an opportunity to revitalize Kiley’s Scaife Gallery landscape and lead by example in the ongoing fight to preserve Modern landscape architecture built in the period of “one great surge of collective energies—the modern movement, an upheaval of traditional values, beliefs and artistic forms”. (1)

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania has the good fortune to harbor two projects by the legendary Modernist landscape architect, Daniel Urban Kiley (1912-2004). His landscape anchors the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Sarah Scaife Gallery addition (1974) in the Oakland neighborhood, and his Agnes R. Katz Plaza (1998) urban square design occupies an important site in the city’s downtown cultural district. Built twenty-four years apart, these designs showcase one semi-private and one public landscape, each displaying different formal solutions yet both utilizing the strong Euclidian geometries, articulated plantings, and interwoven spaces that Kiley is known for.

Sarah Scaife Gallery at the CMoA

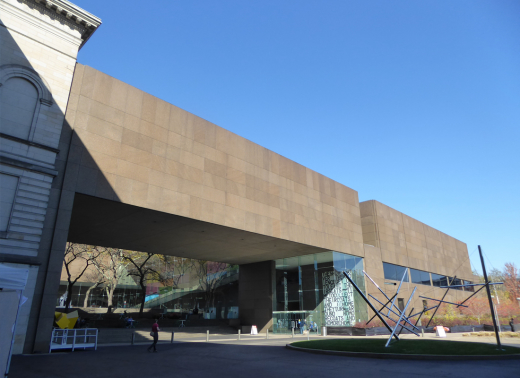

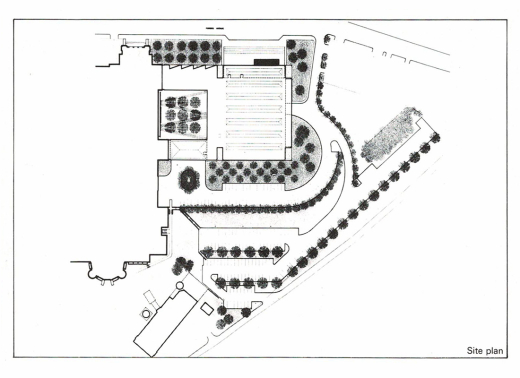

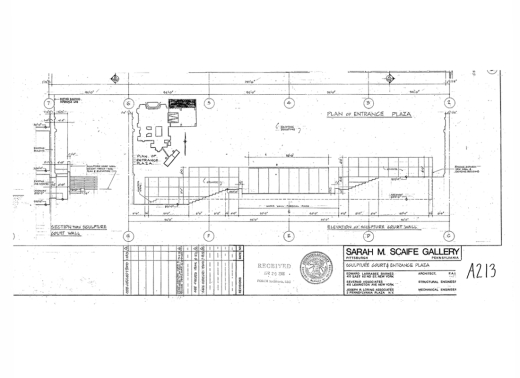

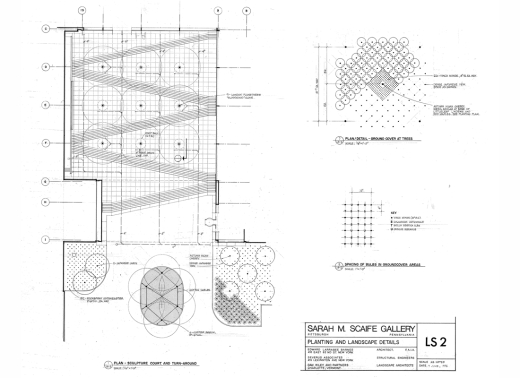

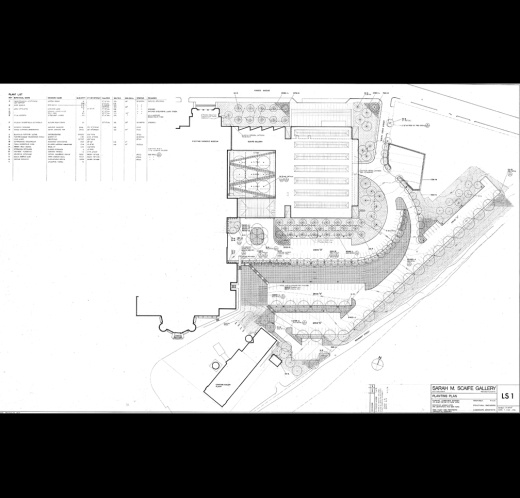

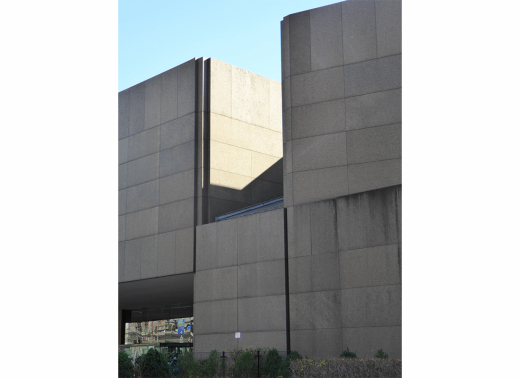

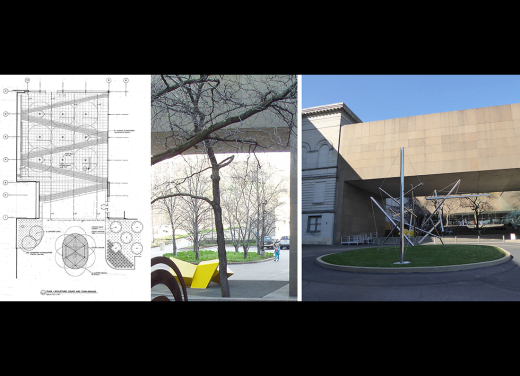

Edward Larrabee Barnes, a repeat Kiley collaborator, designed the Sarah Scaife Gallery addition in 1974. The gallery, an effort spearheaded by then-director Leon Arkus, was a gift to the museum from the Sarah Scaife Foundation and the Scaife family. Barnes enlisted Dan Kiley to execute the project’s landscapes. The Sarah Scaife Gallery, as a large-scale art museum project, successfully joins the existing 1895 Longfellow, Alden and Harlow building, with the needs of a museum intent on expanding its collection. Barnes created a structure similar in mass and scale to the original CMoA building but with its own stylistic identity. The project extends the existing sandstone Beaux-Arts gallery east with a minimalist Norwegian Larvikite monzonite stone-clad housing. The addition required bold, confident landscape moves to provide counter-punching balance. Kiley’s holistic landscape design provides the necessary transition from Barnes’ strong Modernist boxes to the brick row house scale of the neighboring Oakland shopping streets and pedestrian approach off Forbes Avenue. The playful dancing of water feature jets at the entrance along Forbes Avenue draws visitors down the well-proportioned, easy-going steps and into the addition’s inset glass doors. Amazingly, Kiley’s entrance plaza graciously accepted Richard Serra’s COR-TEN steel vertical behemoth, Carnegie, winner of first prize in the 1985 Carnegie International, as if the sculpture had been planned for it from the start.

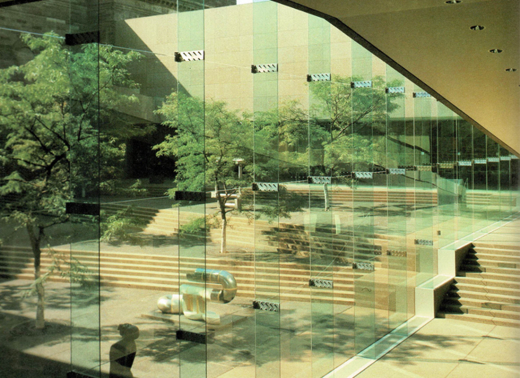

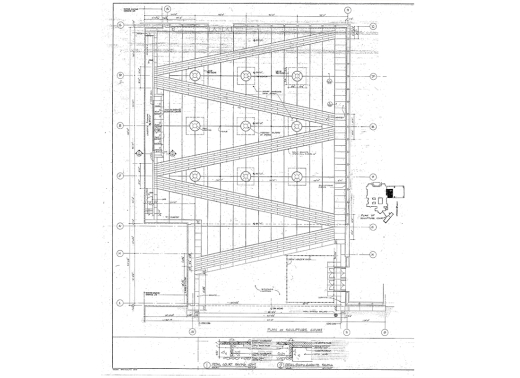

Counterposed against the long rectangular horizontality of Barnes’ and Kiley’s entrance sequence, the rear-facing central sculpture court provides a compact nucleus around which to organize a scheme. The remarkable sculpture court’s triangulated, ascending terraces, with a nine-tree grid, is an intuitive masterpiece of dynamic spatial movement, of nature as art, and an inspired display of two designers obliterating the demarcations of architecture and landscape. Approaching the museum from the southern parking area, one’s gaze is directed under Barnes’ oversized entrance portal to Kiley’s sculpture court. As the gallery form passes overhead, Kiley’s angled court stairs glide upwards as triangular cuts in plan. Honey locust “sculptures” beckon one towards the entrance. Barnes’ building has moments of spatial extension, as is the case with the court’s massive entrance portal: this architectural move provides necessary enclosure to the courtyard.