Making Houston Modern is part of the °®¶¹app Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home.

Making Houston Modern

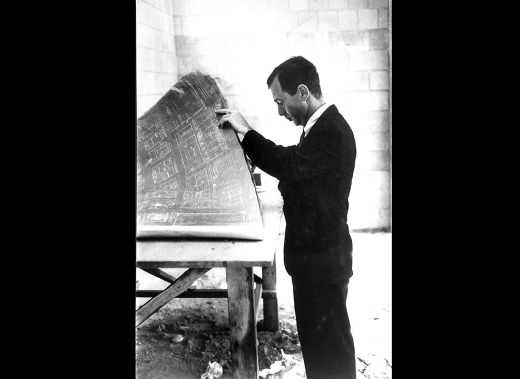

Complex, controversial, and prolific, Howard Barnstone was a central figure in the world of twentieth-century modern architecture. Recognized as Houston’s foremost modern architect in the 1950s, Barnstone came to prominence for his designs with partner Preston M. Bolton, which transposed the rigorous and austere architectural practices of Mies van der Rohe to the hot, steamy coastal plain of Texas. Barnstone was a man of contradictions—charming and witty but also self-centered, caustic and abusive—who shaped new settings that were imbued, at once, with spatial calm and emotional intensity.

Making Houston Modern explores the provocative architect’s life and work, not only through the lens of his architectural practice but also by delving into his personal life, class identity, and connections to the artists, critics, collectors, and museum directors who forged Houston’s distinctive culture in the postwar era.

Making Houston Modern Part One

Why Howard Barnstone Why?

By Stephen Fox and Michelangelo Sabatino

Howard Barnstone practiced architecture in Houston from 1948 until his death in 1987, an exceptionally fertile period in twentieth-century architecture. Barnstone belonged to a generation of American architects born between 1916 and 1929 whose diversity intensifies the question why?... Barnstone valued architectural dexterity. His buildings demonstrated consistency through proportions and details rather than through identification with a set of design principles or methods.

Among the well-known Texas architects who practiced during the postwar period, Barnstone stood out for his rejection of both modernist rationalism and Texas regionalism. Barnstone delighted in defining himself against the dearly held convictions of others. He found support for this propensity in two figures he especially admired: his major client, the Houston businessman and art collector John de Menil (1905–1973), and John de Menil’s other architect, Philip Johnson (1906–2005). John de Menil’s defiance of Houston’s social conventions and Philip Johnson’s skepticism about declarations of faith in architectural movements resonated with Barnstone because both stances seemed to call for individual action rather than acquiescence in group thinking....