The following is an excerpt from by Richard Longstreth, published by Yale University Press in 2010.

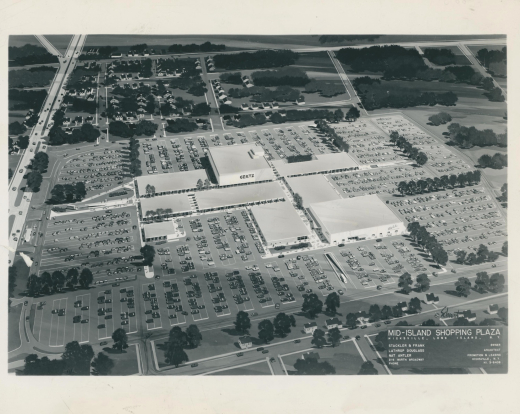

The rise of the regional shopping mall was heralded as a phenomenon of unusual importance well before such complexes became the dominant mode of large-scale retail development. To participants and observers alike, the creation of these enormous complexes, occupying sixty acres or more, with buildings that encompassed from 700,000 to over 1,000,000 square feet, encircled by parking lots capable of holding 3000 to nearly 8000 cars at one time – more cars than could be parked in the downtowns of many modest-sized cities – seemed a remarkable occurrence. Their immense size was matched by their unorthodox configurations, with stores opening inward to tranquil, landscaped pedestrianways. In character as well as scale, they seemed antithetical to the piecemeal complexion of most outlying shopping districts, and their customer-friendly inner sanctums offered a sharp contrast to the sidewalks along streets and parking lots and to the visual cacophony of signs and other accouterments of retail centers generally. The regional mall seemed the ultimate rational response, not just for new outlying areas, but for retail development as a whole. “No construction is more dynamic,” cooed the editors of the Department Store Economist in 1954, “or as likely to influence a reform of the usual urban and suburban hodgepodge of big and little buildings, vacant lots, dumps and slums.” Welton Becket, who became one of the nation’s leading architects of regional malls expressed a view held by many of those involved when he claimed its inevitability. Writing to chain store executives in 1951, when only a single such complex had been completed, he declared: “The regional shopping center became a foregone conclusion when the automobile became a reality.”

What Becket and other champions of the regional mall framed as a direct, logical step in retail development hardly looked that way a few years earlier. After much experimentation in layout during the immediate postwar period, orienting the shopping center to face a large front parking lot became the preferred arrangement for most projects, irrespective of size by 1950. Placing stores along an inner, pedestrian space, on the other hand, was so marginal an idea among retail and real estate interests that it was scarcely recognized, let alone considered as an option. Initially, the mall was championed by architects and planners who called for basic reforms in community design and believed that a pedestrian orientation would foster human interaction and a sense of community focus to new residential areas, qualities they maintained that contemporary, automobile-driven development sorely lacked. But very few such projects had been built and those that had were created under federal auspices, mostly due to the exigencies of World War II. Many designers embraced the concept, but real estate and retail interests remained oblivious. was the catalyst in altering that perspective.

The great respect he commanded from department store and other retail executives made his proposals for Rawls the subject of serious interest that probably no other architect could have elicited in the 1940s. Welch transformed a concept generated by social concerns into one driven by retail needs; he also substantially increased the scale and the scope of goods and services purveyed so that his complexes would serve as “complete” center, ostensibly equivalent in its business functions to the core of a large town or small city. This latter concept was new. J. C. Nichols and other developers of large-scale shopping centers before the war envisioned them as complementary to downtown; they assumed that their generally well-heeled clientele would always rely on the urban core for certain shopping needs. Welch, on the other hand, suggested that his regional malls were a new kind of downtown, surrogates for city centers that had reached capacity.

An equally new idea was that the department store branch was the key component to achieving equivalency. Theretofore shopping centers and department store branches had developed independently of one another, Strawbridge & Clothier’s first branch introduced to Suburban Square at an early stage being the primary exception.