The Modern architecture movement in the United States has a rich but complicated history, one that °®¶¹app is committed to explore, even as we advocate for its preservation. This history is closely intertwined with that of Modernism in Europe, but the post-war American version has its own flavor and context, driven by our own unique demographics, economics, cultures and politics. Out of that complex mix arose countless examples of innovative, thought-provoking architecture and landscape, both by transplanted Europeans and by our own home-grown American practitioners.

Several aspects of that, however, are less admirable and merit further examination to understand the true and complete story of Modernism. While one can argue direct causality or lack thereof, it must be admitted that the rise of post-war Modernism also coincided in time with the rise of the suburbs, white flight to those suburbs, the construction of the interstate highway system (often through historic neighborhoods of color), the emptying out of downtowns, the abandonment or neglect of transit systems, and many more impacts that are regretted today.

President's Column January 2023: Revisiting Urban Renewal — a Challenge and an Opportunity

Author

Robert Meckfessel, FAIA

Affiliation

°®¶¹app President

Tags

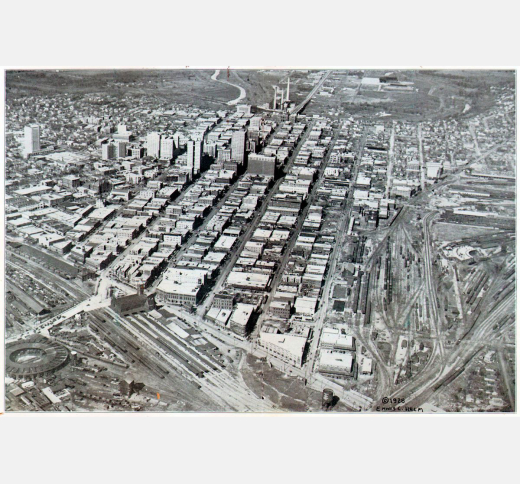

Again, these sins cannot be laid entirely at the feet of the Modern Movement, as there were many other factors and motivations in play — some well-meaning, some venal — but there is a marked intersection among them in the topic of urban renewal programs (as practiced in the US in the 40s, 50s and 60s) when expansive swaths of American inner cities were cleared to create space for large-scale redevelopment programs, with promises of health, beauty, and prosperity. The planning for these new developments in these cleared tracts was very often based on Modernist principles, and the buildings that rose on them were primarily Modernist in character.

Sometimes urban renewal programs actually succeeded, at least to a degree, and new neighborhoods and communities rose that are still with us today, vibrant and successful. But often as not, the story of these redeveloped areas is much more complex, with high levels of displacement, increased economic and ethnic segregation, ill-sited freeways, and blocks of anonymous residential and office towers, all at the cost of once-vibrant neighborhoods.

It’s a mixed bag, to be sure. Here in my part of the world in North Texas, the post-assassination program resulted in the loss of historic fabric, but also in the creation of significant buildings including I.M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall (it’s controversial, I know, but I like it a lot). In Fort Worth, the vibrant Hell’s Half-Acre neighborhood was cleared to create room for a new, modern, convention center (not particularly esteemed) and for the lush and lovely cascades of the Water Gardens by Philip Johnson.

This is not an easy subject, we know, but °®¶¹app has always prided itself on digging beneath the surface of Modernism, beyond the “cool” factor, so to speak, to understand its true roots, impacts, and qualities.

Hence, our annual theme of Revisiting Urban Renewal. We’ll be talking a lot about that this year: the National Symposium in New Haven will dig deeply into the topic of the “Complexities of the Modern American City;” the theme will be explored in many local tours during Tour Day in the fall; we are seeking and for an Urban Renewal-themed special edition of the newsletter; and our social media posts will cover the topic as the year progresses. If you have thoughts, experiences, or information on the topic, please feel free to share them with us. We’re going to learn a lot this year.

Robert Meckfessel, FAIA