Nicole D. Santiago, the recipient of °®¶¹app Northern California (NOCA) Chapter’s 2018 Travel Grant for Students & Emerging Professionals, writes about her experience attending the 2018 National Symposium in Columbus.

Championing preservation tends to imply a view oriented toward the past. But after attending the National Symposium in Columbus, I was most inspired by how dynamic and forward thinking °®¶¹app is. °®¶¹app was created in the late 1980s as a protective force to shield modern architecture during a time when many architectural marvels were at risk, but the scope of its mission has greatly expanded. Rather than focusing squarely on the past, today °®¶¹app asks, “Now what?” and this relative state of security is fertile ground for innovation and “progressive preservation.”

My favorite panel, Interpreting Residential Modern, explored how the forward-thinking spirit that defined modernism continues to propel the historical movement into the future through fresh takes on the traditional ‘house museum’ model. The spaces the panelists have worked with aren’t merely time capsules—they’re more like crucibles where old and new combine, creating a bridge over temporal and cultural divides. The first speaker, Jorge Otero-Pailos, had me truly thinking outside of the (glass) box. Otero-Pailos, Director and Professor of Historic Preservation at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, spoke to us about his project, An Olfactory Reconstruction of the Philip Johnson Glass House, 2008. He conjured elements, such as water damage and cigarette smoke, that we’ve traditionally sought to correct and challenged the audience to consider what it would look like to embrace or even accentuate these qualities. He believes these sensual endeavors are truer to what a space would have been like for those experiencing it during its most lively era.

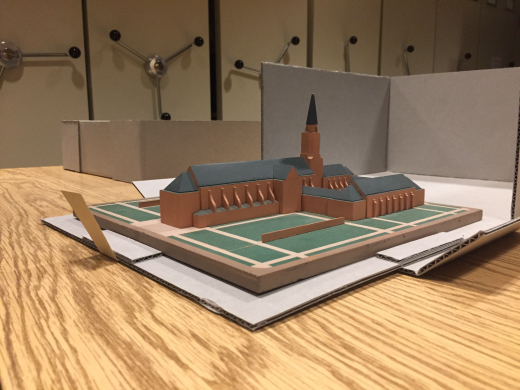

The next panelist was Kevin Adkisson, Collections Fellow at the Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research. He walked us through how different residences-turned-museums on the Cranbrook Center’s campus have become staging grounds for new artistic interventions. By inviting artists to occupy and transform Saarinen House, a residence designed by Eliel Saarinen for his family to live in while Saarinen served as Cranbrook’s first resident architect and the Art Academy’s first president and head of the Architecture Department house, Adkisson’s goal is to “frustrate expectations to incite conversation,” a phrase that stayed with me long after the panel. Adkisson himself has also created more traditional, but nonetheless fresh installations in the Saarinen House. In one exhibit, he set up drafting tables in the studio populated with reproductions of archival material that could be handled and flipped through, such as sketches, plans, and presentation drawings of furniture and buildings, as well as period books, articles, and catalogues by or about the Saarinen family. This staging idea provided visitors an excellent new way to experience the space.

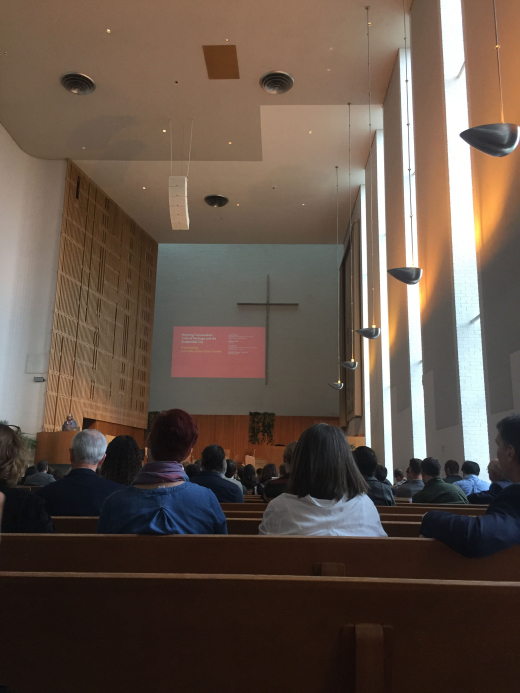

Oh, and did I mention that the symposium panels took place in amazing spaces?! I’ve never been in so many churches in one weekend, not to mention churches like these. The St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, designed by Gunnar Birkerts, features a sweeping cascade of pews and a harmonious combination of natural light and artificial light, most notably from an eighteen-foot-diameter light fixture suspended below a central skylight.