In recent months, a number of iconic buildings and sites that were completed during the 1980s outside of the chronological period that most associate with the Modern Movement, and generally assumed to be outside °®¶¹app’s purview, are under threat of demolition and-or radical transformation.

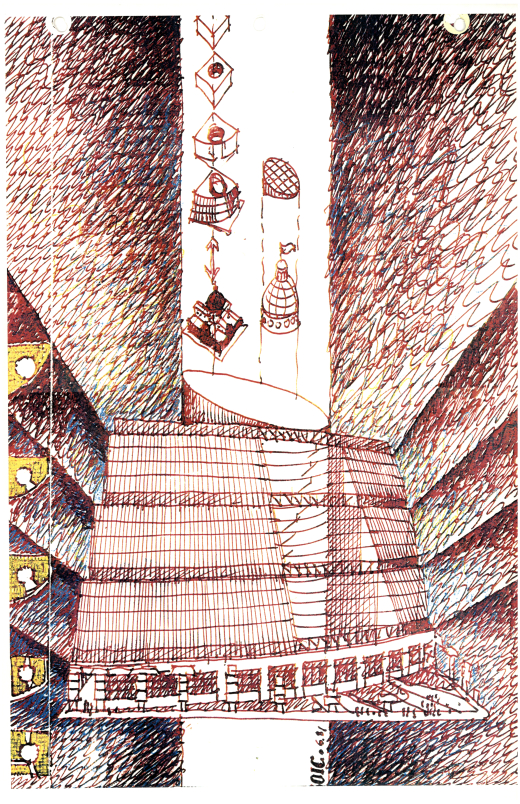

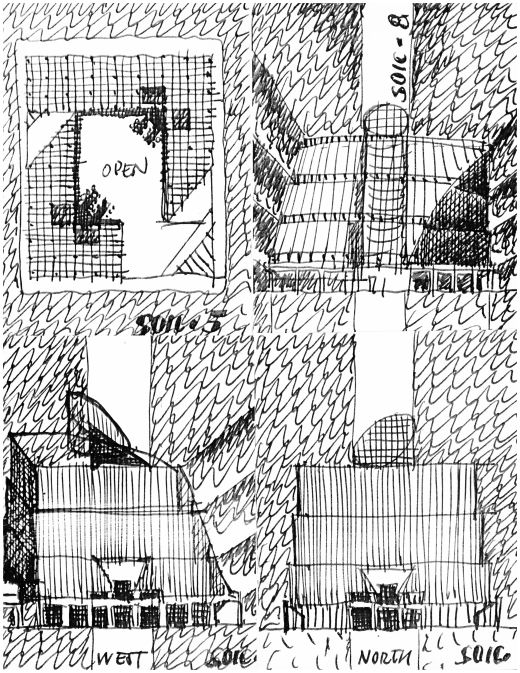

In New York, Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s (550 Madison Avenue) opened in 1984, is currently being ‘renovated’ by the architectural firm Snøhetta. In Chicago, the State of Illinois Center (James R. Thompson Center) by Helmut Jahn (Murphy/Jahn) opened in 1985, has been at the center of heated public debate over whether the State of Illinois should sell the building to developers (Nathan Eddy recently produced a thoughtful documentary on the Thompson Center entitled (2017)). A sale puts it at risk of demolition whereas adopting a preservation and adaptive reuse strategy would ensure that the life of this significant building could be extended. Although young by some landmarking standards, the Thompson Center would certainly qualify under at least six, if not all seven criteria, of the Chicago Landmarks Ordinance and should be so recognized.

At first glance the ‘baroque’ and monumental Thompson Center seems to share little with the Modern Movement, especially for those who understand this expression as an orthodox and static framework. The light-filled Thompson Center atrium takes spatial cues from John Portman’s commercial buildings and deploys color to temper the impact of industrial materials in ways similar to Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers Centre George Pompidou (1977); the curved façade seems to point to a rejection of the austere rationalism associated with the Modern Movement especially if one compares it to the somber Chicago nearby designed by Mies van der Rohe (1959-1974).

And yet, this is hardly the case: a more attentive reading reveals a strong continuity with modern building materials, types, and technology. It is worth noting that Jahn jumpstarted his career in Chicago after arriving from Germany by working with the design team lead by IIT College of Architecture graduate Gene Summers (C. F. Murphy Associates) for the Mies-inspired convention center (commonly referred to as the Lakeside Pavilion) completed in 1971. It is another highly significant Chicago modernist building and site that should be landmarked. More indirect continuity with the Modern Movement is to be found with Philip Johnson. Although the tongue-in-cheek Chippendale citation of the AT&T building shares little with the steel and glass aesthetic of the Seagram Building (1958) it is still a “tall building,” a type typically associated with modernity and modernism.