The following is adapted from an assignment for the class Modern American Architecture on the Historic Preservation program at GSAPP, Columbia University. Discussing the global impact of New Brutalism and the attempt to reinstall ethics and humanism into architectural design, it examines the works of Louis I Kahn, his connections to C.I.A.M. and the three-phase plan for the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

1959 was a key year in architecture; in an Oedipal moment, British architect Peter “Brutus” Smithson realized the bloody nature of his university sobriquet. Murdering C.I.A.M. (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), he dethroned Le Corbusier and attempted to take his place as the de facto leader of built design for the next generation. Smithson, along with his fellow architect and wife Alison Smithson and inner circle, Team X, had waged a decade-long war against the old guard’s machine aesthetic. Fashioning a New Brutalism, they waxed lyrical with critics, calling for a Ruskinian pivot to truth and humanism in architecture. Yet today, the movement is rarely identified as either. Shunned for decades as hard architecture, the general public view Brutalism today through its aesthetic: an architectonic of mass dressed in concrete.[1] Similarly, few historians cover the critical discourse and the ethics it embodied. This text returns readers to the dawn of the movement, the rebranding of European modernism and the global nature of the debate. Studying works by Louis Kahn, it demonstrates the architect’s connections with early Brutalism and its impact on the unbuilt three-phase plan for the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California.

The Salk Institute and the Lost Ethics of Brutalism

Author

James E. Churchill

Tags

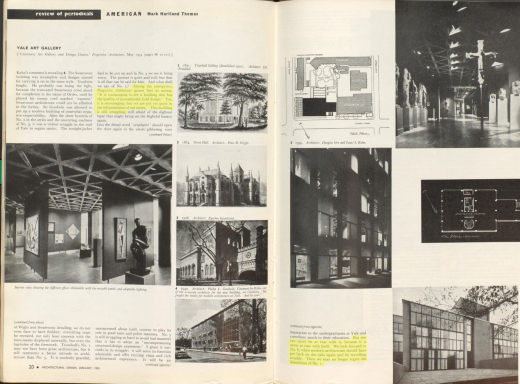

New Brutalism as a term had Swedish origins but was coined in the mid-1950s by the Smithsons and the critic Reyner Banham in a pointed barb against New Empiricism or welfare-state architecture in British council planning. Aiming for a humanist revival, the message was confused at best. In January 1955 the Smithsons defined the movement as holding a “reverence of materials,” but two years later claimed, “up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical.”[2] Banham spent a decade debating the dichotomy that culminated in his 1966 book, The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? Yet the answer remained cryptic. Despite concluding Brutalism “never quite broke out of the aesthetic frame of reference,” Banham maintained it injected morals into staid design.[3] Louis Kahn’s work was identified as an early pioneer. Drawing comparison to the Hunstanton school by the Smithsons, the Yale University Art Gallery was commended for leaning “heavily on the frank expression of structure and materials,”[4] but poo-pooed for a lack of transparency. Banham fell afoul of his title, obsessing on Kahn’s glazing and “secretive” plan, missing a design that reflected the streetwall of the predecessor gallery across the way and a scale echoing the town’s built environment. Viewed in terms of their humanist tendencies, the gallery appears eminently more superior. Yet, what exactly were they attempting to achieve and where did their thought process come from?

Despite the Smithsons’ claim to Brutalist fame, the concepts provided were neither new nor their own. Some ten years earlier, secretary-general Sigfried Giedion, José Luis Sert and Fernand Léger wrote that, “people want buildings that represent their social and community life.”[5] Ideas were similarly percolating across the pond. When the mantle was passed at C.I.A.M. X, Smithson surprised many by handing over the keynote speech to an older American, Louis Kahn, in honor of the human scale and organic nature of his work in Philadelphia. The love appeared, however, unrequited. Kahn used the podium to critique in-fighting in the organization and stressed the need to stop over-academizing process; ironic given urban planner Edmund Bacon had rejected his designs for similar reasons. The Smithsons’ choice, however, was informative. While neither party achieved urban utopia, Kahn’s work is, unlike the Smithsons’, rarely connected with the Brutalist canon and today labelled as American “monumentalism.”

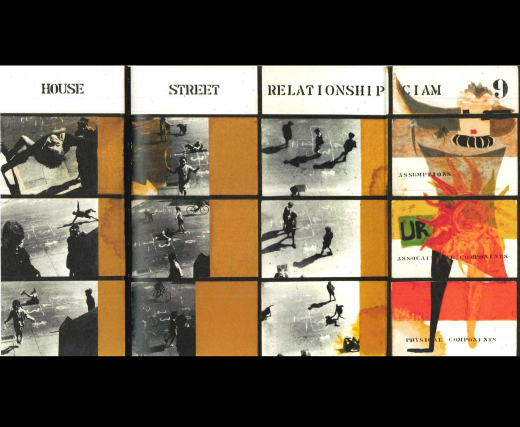

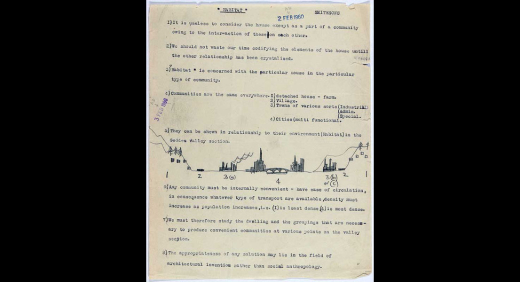

The genesis of Brutalism emerged from Le Corbusier’s opening address at C.I.A.M. VII in 1949. Exclaiming early modernism obsolete, the architect urged a speedy replacement of the Dwelling, Work, Recreation, Circulation hierarchy formed in the Athens charter for one of habitat. Yet, work towards his new charter was painfully slow. C.I.A.M. VIII, entitled “heart of the City,” envisaged a built environment with “five ascending scales of community” – “the village,” “neighbourhood,” “city sector,” “city,” and “metropolis,” but little came of it, and it was not until C.I.A.M. IX in 1953, the Smithsons, emboldened by their Hunstanton school competitive win, went on the attack.[6] Joining Aldo Van Eyck, Jacob Bakema, Georges Candilis, Shadrach Woods, John Voelcker and William and Jill Howell, they eviscerated machine living: “‘Belonging’ is emotional need… The short narrow street of the slum succeeds where spacious redevelopment frequently fails.[7]

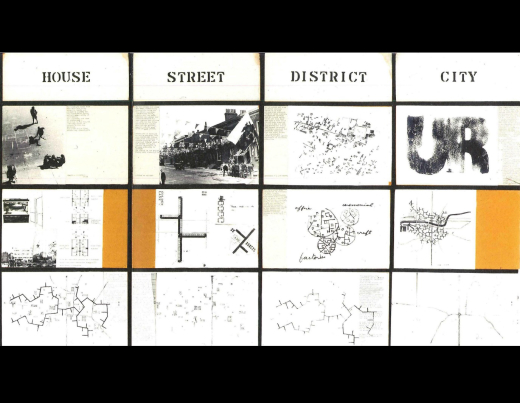

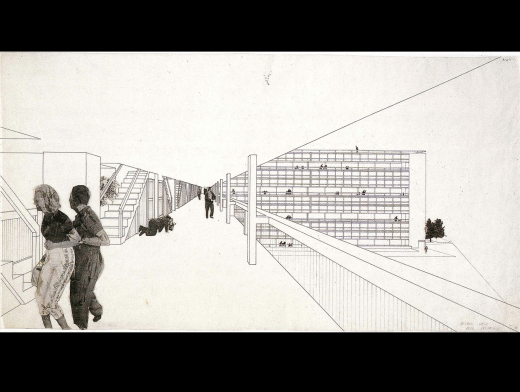

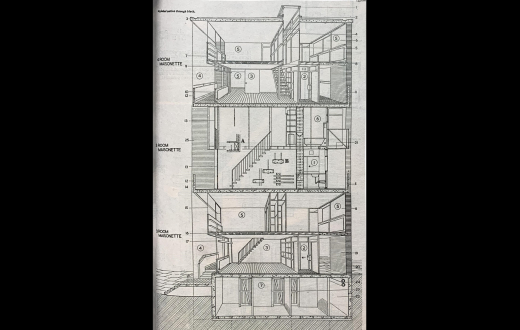

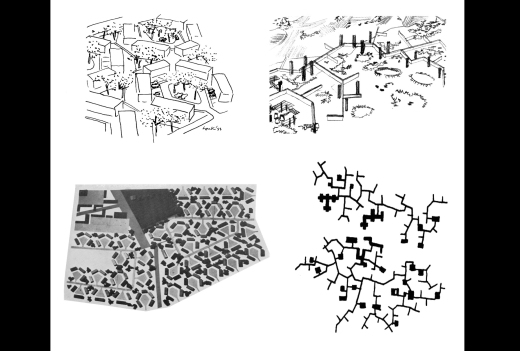

Appropriating the C.I.A.M scales, the Smithsons aligned with the photographer Nigel Henderson to create the “Urban Reidentification Grid,” an amalgamation of photographs depicting lower class child play and sketches that pushed human interaction over function as the key to social cohesion. Rebranding the catechism as House, Street, District, City, the Smithsons used their Golden Lane project as a case study. Alluding to the adage of “the good old days,” units emulated Victorian archetypes. Each flat was triple-story and connected through internal, not external, staircases. Access to the street was through the front room lounge, removing the need for dark internal corridors, as in the English maisonette. Decks were widened every three levels, giving more room to the upper and lower bedrooms and providing enlarged meeting places for neighbors. Architectural drawings utilized collage to paste celebrities into the scene, with other phases positioned in the background of perspective drawings, emphasizing connectivity of adjacent districts. In contrast to Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation, criticized by the Smithson’s for its separation from the surrounding city, the programme rejected single block and grid housing for organic networks of low-rise housing, overlaid on a bombed-out city footprint. In 1954, Team X codified this habitat in the Doorn Manifesto.

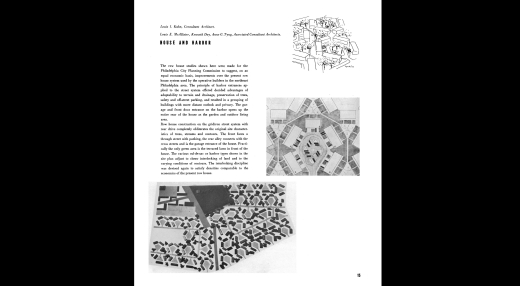

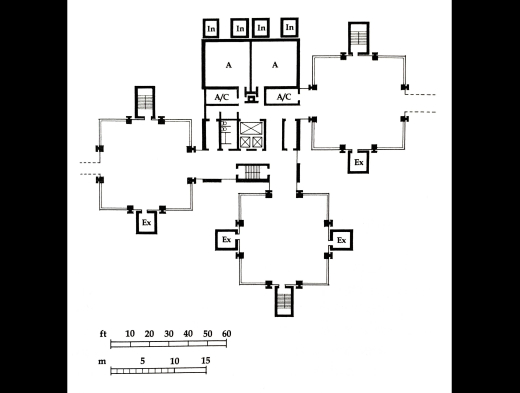

Despite the stark difference in politics and economics, the shifting times had not been lost 3,500 miles away in the United States. Louis Kahn’s 1953 plan for Midtown Philadelphia touched heavily on the kind of density and interconnected neighborhood planning that was the foundation of the manifesto. “House and Harbor” defied the American gridiron street system for an interlocking discipline not wholly unlike that suggested by the Smithsons in their Golden Lane project.[8]

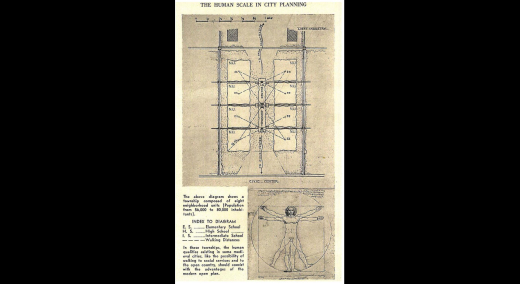

Kahn’s concepts from a 1957 Yale architectural magazine article demonstrate the architect’s fluency with C.I.A.M.’s catechisms and concepts, “A street wants to be a building… Center City is a place to go to – not go through… Decentralization disperses and destroys the city.”[9] At C.I.A.M. XI, Kahn offered solutions to Team X’s urban regeneration conundrum. Organic movement was key, with affinity to the city as a living organ. Echoing J. L. Sert’s 1944 “The human scale in City Planning,” a heart-like system of eight highly connected ventricle “neighborhood units,” he pressed the need to consider the nature of buildings and streets and not simply the programmatic function that preoccupied the first-generation modernists.

Kahn, who had made his name with the Yale Art Gallery, established further fame with the Biological and Medical Laboratories for the University of Pennsylvania. In 1957, MoMA asserted it was “probably the single most consequential building constructed in the United States since the war.” Critics state Kahn was experimenting with the human condition that saw a maturation of his style.[10] The condition aligned Kahn to architectural phenomenology, a quasi-philosophy rooted in pure experience of space and an intellectualization of building practice that was playing out in Brutalist theory.[11] At Richards, Kahn created a plan of four offset towers, one mechanical and three laboratories, articulating function through form and material. The mechanical tower was purposeful, a single mass of cast-in-place concrete, a counterpoint to the laboratories that were impregnated with light through intermittent blocks of glazing, supported by the brawny concrete frame. Previewing metabolism of the 1980s, offices plugged into the building like escape pods, while the fenestration and interconnected circulation corridors maintained a visual street. The laboratory footprints appeared as deliberate sections in a pin-wheel system that permitted centrifugal growth. A core center supporting periphery functionality evokes similarity to the human body.

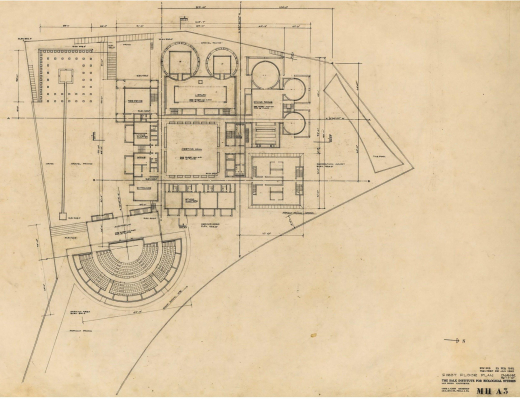

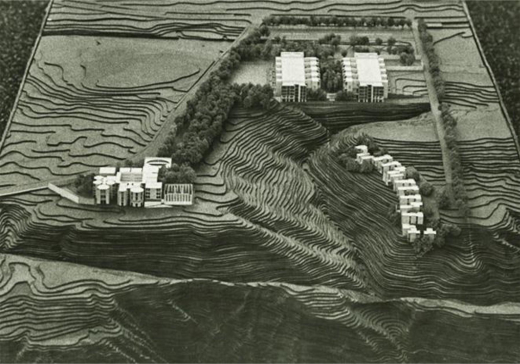

The Salk project, begun some two years later, enabled Kahn to extend his Richards vision and summon the true essence of the C.I.A.M. habitat. Jonas Salk, gifted 27-acres in Torrey Pines, San Diego for services to humanity, tasked the architect to create a master plan for a world-class center of biology. A key success of the Salk Institute was the symbiotic relationship between architect and client. Salk and Kahn’s meetings discussed function but also two notably humanist end-goals in the design: the need for scientists to express themselves through art, and to share their discoveries with all humankind. Both elements were integral (“art involves choice, and everything that man does, he does in art”), while contemplation and interaction were to be weighted just as equally to the task at hand; “this consideration changed the Salk Institute from a plain building like the one at the University of Pennsylvania to one which demanded a place of meeting which was in every bit as big as a laboratory.”[12] These concepts would permit the institute to transcend an Athens hierarchy of just dwelling or work to become a place that celebrated humanity, one that had evaded architects throughout the machine age. While funding issues and disagreements plagued the project, mutual respect and patience led to a final third design that both men embraced.

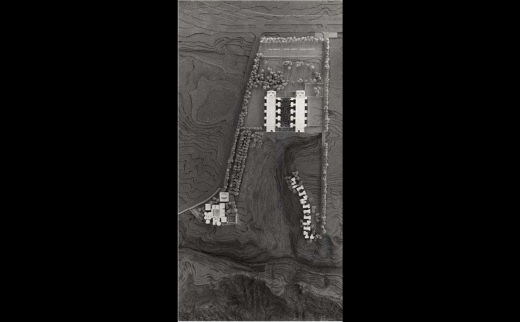

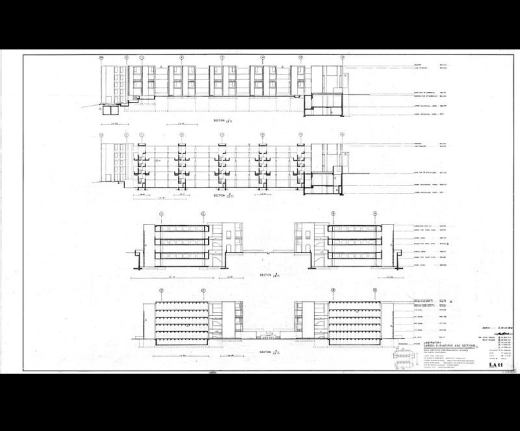

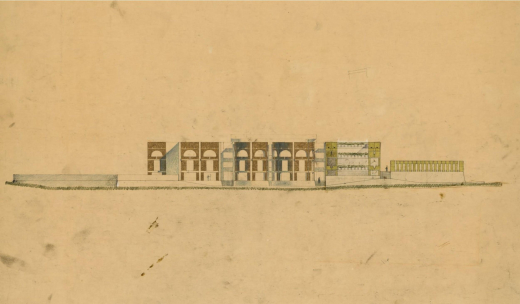

Composed of the Meeting house, the Laboratory and the Living place, hierarchy was stipulated by spatial positioning, typology and material. Kahn conveyed unity through a limited palette of natural materials. Restricted by stringent codes on building heights and challenging topography, Kahn located the Laboratory and the Meeting House at similar heights above sea-level despite their notable separation. Placed on platforms, the former, inland and at a higher elevation, demonstrated formidable design prowess with sub-grade light wells and centralized patios, but was no match for the latter’s soaring, fifty-foot walls and triple-height meeting hall, intended to entertain dignitaries with uninterrupted views of the Pacific Ocean. The Laboratory was formally axial with two symmetrical wings, while the Meeting house was emphasized through a heavy asymmetric massing of varied Platonic solids. The Living Space, placed across the canyon from the Meeting House and a lower overall elevation, was a simple agglomeration of low-density villas placed along a serpentine street. In each, materials demarcated functionality. Relaxation areas were to be made of stone ashlar (later concrete) and teak, while poured concrete and steel were to be used for work areas. Despite cancellation of work on the Meeting and Living Place in 1963 due to lack of capital, Kahn demonstrated their importance in the overall scheme by retaining them in drawings throughout the design process.[13]

As with Richards, buildings seemed anatomical with each area having a central core, but the size of the land mass allowed function to be considerably more developed. Independence remained a high priority, with each study separated from work by a kind of umbilical circulation that extended from the Laboratory. The Living Place and Meeting Place incorporated similar answers with cuboidal living and study spaces for individuals. Where space was to be shared, Kahn espoused large open-plan rooms. The street was emblematic of the district, with the Living Place composed of varied footprints, alternating window exposures, and a curved road that rose and dipped with the undulating terrain of the mesa. The Laboratory and Meeting Place, however, shared a tree-lined boulevard with orthogonal circulation, fenestration and landscaping throughout. Despite unique identities, this tri-cluster neighborhood was woven together through consistent visibility and passage that maintained connectivity to themselves and the outside world. The Meeting Place and its auditorium, library and meeting hall were the zenith, allowing the institute to mediate relations within the city of San Diego and beyond.

Due to a sad twist of semantic fate, the general public paints an ever-larger diversity of buildings with the Brutalist brush. In a blog post on the Salk Institute, a writer in 2017 noted that a tour member incorrectly said the building “was a Brutalist project because it was extreme in nature.”[14] There remains an urgency to educate people as to the ethics of Brutalism and the humanism that was intrinsic to the movement. The noun used by Kahn of the Salk was in fact “wonder,” and he stated, “presence of the sky, earth and sea is a reminder of wonder. Wonder is the beginning of all knowledge.”[15] Both Salk and Kahn were sensitive to the power of nature to inspire art in humankind and the need to share inspiration. Yet today, the Laboratory, shares the mesa and canyon with neither the Living Place nor the Meeting Place, but with a sewage pumping station and a “sprawling parking lot.”[16] The legacy left by Kahn is recognized as one of the greatest in the history of architecture, but his oeuvre should not be pigeon-holed into an American “monumentalism;” he was highly motivated by global trends. Jorge Otero-Pailos wrote that the phenomenologists “called into question the accepted conventions of architectural historiography… they raised the possibility that a building’s meaning might be more accurately ascertained through the direct physical experience of the building itself.” Such discussions remain relevant to our analysis of Brutalism and Kahn’s work that regularly incites a feeling of spirituality within visitors. Team X saw Brutalism as a silver bullet to reinject truth and humanity into architecture, and arguably the unbuilt Salk Institute was a distillation of these beliefs in the United States.

The author would like to thank Kyle Normandin of Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. for his early support of this project.

About the Author

James E. Churchill is a Funaro Scholar and graduate of the MS in Historic Preservation at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) of Columbia University. Sharing a wide range of interests that straddle architectural history, design and material sciences. He is an active participant with the newly formed Material Sciences committee at The Association for Preservation Technology (APT), and holds memberships also at the American Institute for Conservation (AIC/FAIC), ASM International, American Ceramic Society and the Association for Iron and Steel Technology (AIST). He received an honor award for outstanding thesis in historic preservation for and has subsequently published for ASM International (September 2020 issue of AM&P Vol. 178 No. 6) and an article in JOM entitled (October 2020 issue of JOM Vol. 72 No. 10).

James previously published an essay during the demolishment of the Union Church in Hong Kong, which on the °®¶¹app International website.

Notes

[1] Critics decried the coldness of Brutalism’s main material identifier, concrete. Behavioural psychologist Richard Sommer wrote “Brutal buildings are a response to a brutal society” placing it firmly in a dystopian social context. See Richard Sommer, Tight Spaces; Hard Architecture and How to Humanize It (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974). This text will conflate the terms New Brutalism and Brutalism in the ensuing pages for convenience.

[2] The term gained traction with Theo Crosby, Alison Smithson, and Peter Smithson, "The New Brutalism," Architectural Design 25, no. 1 (January 1955): 1; Reyner Banham, "The New Brutalism," The Architectural Review (December 1955); Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson, "The New Brutalism," Architectural Design 27, no. 4 (April 1957): 113.

[3] Reyner Banham, The New Brutalism: Ethic Or Aesthetic? (London: Architectural Press, 1968), 135

[4] Banham, The New Brutalism: Ethic Or Aesthetic?, 44.

[5] José Luis Sert, Fernand Léger, and Sigfried Giedion, "Nine points on monumentality," Architecture culture 1968 (1943).

[6] Hadas Steiner, "Life at the Threshold," October, no. 136 (2011): 133.

[7] Team X response to C.I.A.M. 8 report, 1951 in Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 4th ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 271. .

[8] Found in 'House and Harbor,' Louis I Kahn, "Toward a plan for midtown Philadelphia," Perspecta 2: The Yale Architectural Journal (1953): 14.

[9] Louis I Kahn, "Order in Architecture," Perspecta 4: The Yale Architectural Journal (1957): 58.

[10] See William Curtis, "on monuments and monumentality: louis i. kahn," in Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Phaidon Press, 1996), 513; Leland M. Roth and Amanda C. R. Clark, "Silence and Light: The Architecture of Louis I. Kahn," in American architecture : a history (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016), 459.

[11] See Jorge Otero-Pailos, Architecture's historical turn : phenomenology and the rise of the postmodern (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

[12] Peter Inskip et al., "Conservation Management Plan : Salk Institute for Biological Studies," ed. Deborah Slaton, Tim Penich, and Tiffany Olson (2016), 46.

[13] Louis I. Kahn, Louis Kahn : conversations with students (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 18, 25.

[14] "The Salk Institute," Life of an Architect, updated November 1, 2017, accessed October 24, 2020, .

[15] Document, Abstract of Program, 030, Series II, Box A, Folder 2716, The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania.

[16] Inskip et al., "Conservation Management Plan : Salk Institute for Biological Studies," 280-1.

Bibliography

“About Salk Architecture,” Visiting Salk. Accessed February 28, 2019.

Augustyniak, Mairan and Entwhistle, Jr., Fred T. “Survey on New Brutalism,” letter to Louis Kahn dated Pittsburgh, PA, 14 April 1957. LIK 59

Bakema, Van Eyck, van Ginkel, Hovens-Greve, Smithson, and Voelker, Doorn Manifesto, Doorn: C.I.A.M. Meeting 29-30-21, January 1954.

Banham, Reyner. “New Brutalism” in The Architectural Review. December 1955.

———. New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? Stuttgart: Karl Kramer Verlag, 1966.

Borson, Bob. “The Salk Institute.” Life of an Architect. Accessed May 4, 2019.

Chamberlin, Powell. "Housing in Golden Lane, London.". Architectural Review 121, no. 6 (June 1957): 414-26.

Chasin, N. B. (2002). Ethics and aesthetics: New brutalism, team 10, and architectural change in the 1950s. From ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (276322906). Accessed March 20, 2019

Curtis, William J. R. Modern Architecture since 1900. 3rd ed. London: Phaidon, 1996.

Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. 4th ed. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 2007).

Giedion, S. A Decade of New Architecture / Edited by S. Giedion = Dix Ans D'architecture Contemporaine. Zurich: Girsberger, 1951.

Inskip, Peter, Stephen Gee, Liz Sargent, Kyle Normandin, Ann Harrer, Kenneth Itle, and Timothy Crowe. "Conservation Management Plan : Salk Institute for Biological Studies." edited by Deborah Slaton, Penichm Tim and Tiffany Olson, Oct 2016.

Kahn, Louis I. "Monumentality." In Zucker, Paul New Architecture and City Planning. A Symposium. New York: Philosophical Library, 1944.

———. “Order in Architecture.” Perspecta 4: The Yale Architectural Journal, 1957.

———. ‘House and Harbor’ in “Toward a Plan for Midtown Philadelphia.” Perspecta 2: The Yale Architectural Journal, 1953.

Leslie, Thomas, and Louis I. Kahn. Louis I. Kahn : Building Art, Building Science. 1st ed. New York: George Braziller, 2005.

Moe, Kiel. "Extraordinary Performances at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies." Journal of Architectural Education. 1984- 61, no. 4, 2008. Accessed February 28, 2019.

Ronner, Heinz, Sharad Jhaveri, and Alessandro Vasella. Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-1974. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1977.

Roth, Leland M., and Amanda C. R. Clark. American Architecture : A History. Second edition. ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2016.

Sert, José Luis, Fernand Léger, and Siegfried Giedion. "Nine Points on Monumentality 1943." Harvard Architecture Review. Spring 1984.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. “The New Brutalism.” In Architectural Design 27. April 1957.

———. "The New Brutalism,” in Architectural Design 25, no. 1. January 1955.

———. "The as Found and the Found." In The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, edited by David Robbins. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990.

Social, Group for the Research of, Visual Inter-Relationships, and Oscar Newman. New Frontiers in Architecture. Universe Books, 1961.

Steiner, Hadas. "Life at the Threshold." October 136 (2011): 133-55.

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., Inskip and Gee Architects, and Liz Sargent HLA. Conservation Management Plan.

Zucker, Paul. New Architecture and City Planning: A Symposium. Philosophical library New York, 1944.