American Architecture in the 1970s was fraught with divergent reactions to Modernism and responses to sociopolitical and environmental crises. The decade was one of exploration, experimentation, and reckoning that would shape the directions of architecture through remainder of the twentieth century. As the 70s turn 50, we are faced with the new task of trying to comprehend and contextualize these buildings, sites, and landscapes in order to steward them into the future.

Architecture faced a crossroads in the 1970s. Many architects felt that the utopian promises of Modernism to build social change and a new, better world through an architecture of functionalism, material honesty, and new technologies had failed—or at least had been corrupted by commercial developers. Public sentiment turned against urban renewal and the austere and imposing projects that seemingly only other architects could love. The question of what would come next, though, resulted in a fractured decade of varying trends—some that led to dead-ends, and others that had lasting legacies through the end of the century. The following provides a small taste of some of the directions, movements, and “schools” in American architecture in the 1970s.

In the early part of the 1970s, the Modernist trends of the previous decades continued. As with any decade—there is no hard start and stop when it comes to design evolution. Examples of Late Modernism (including Glass Skin architecture), Brutalism, New Formalism, and Late Expressionism—in some cases, designed in the 1960s and not completed until the following decade—were built well into the 1970s. Variations of Miesian glass and steel buildings shifted toward mirror glass, taut skins, and High Tech Structuralism. The space age and rising concerns about environmentalism also spurred more radical “paper architecture” (Ant Farm in the US, and Superstudio, Archigram, etc. abroad), space fames, and Metabolist designs (as exemplified at the Osaka ’70 Expo), which took the Modernist interest in technological and structural solutions in surprising new directions. Divergent reactions to mainstream Modernism also included a mix of vernacular forms and materials, including, organic, ecologically-minded shed roofs, wood shingles and wood siding of the Sea Ranch on the West Coast and Robert A. M. Stern’s reinterpretation of the Shingle Style on the East Coast. Earth tones and traditional materials like wood, brick, and terra cotta were used as veneers to balance and soften spaces of concrete, steel, and glass. Pyramidal and triangular forms break from the Modernist box. Historicism and vernacular forms also became increasingly acceptable as Postmodernism, which would come into maturity in the 1980s, was also beginning to enter the mainstream in the latter half of the 1970s and as the historic preservation movement became more nationally established and professionalized.

The '70s Turn 50: Divergences in American Architecture

Author

Hannah Simonson

Affiliation

Architectural Historian/Cultural Resources Planner, Page & Turnbull President, °®¶¹app/Northern California

Tags

Emerging Critques of Modernism

Whereas Le Corbusier's Vers une architecture (Towards a New Architecture, 1923) was the seminal text of the Modern Movement—particularly the functionalist International Style—perhaps the most influential theoretical text for the architecture after Modernism was Robert Venturi's Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. Published in 1966, just five years after Jane Jacob’s critique of Modernist urban planning in Death and Life of Great American Cities, Venturi challenged the orthodoxy of functionalist Modernism and expressed a desire for complexity and contradiction in architecture that would reflect the "messy vitality" of contemporary society, and did not shy away from historical and vernacular sources for inspiration. Venturi’s famous quip “less is a bore” was a direct dig at Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more.” His subsequent book, co-authored with Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, Learning From Las Vegas (1972), celebrated the "honky-tonk" elements of the commercial vernacular and launched the famous "duck" vs "decorated shed" critique of Modernism. While Complexity and Contradiction provided a polemic against establishment Modernism, it did not set forth a fully formulated aesthetic agenda, manifesto for a particular new style, or even guidelines for a new approach.

Charles Jencks's Language of Post-Modern Architecture, which was first published in 1977 with a number of subsequent editions, helped to provide a framework for thinking about, formulating, and understanding the burgeoning architectural movement diverging from Modernism. Jencks also helped to push forward the notion that architecture should communicate through legible symbols, metaphors, or other semantic systems of meaning. Postmodern architecture opened up space for humor, irony, pluralism, historicism, vernacular, and low-brow honky-tonk to be part of contemporary architecture.

In a shocking twist of events, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City mounted an exhibition in the mid-1970s that revisited the architecture of the Ècole des Beaux-Art, the French school that stood for everything that Modernist architecture claimed to oppose. In the introduction to the catalog, curator Arthur Drexler observed that history has been written by the victor—the Bauhaus and its Modernist lineage—and critiques the myopic "anti-historical" attitude that he saw in Modernist architects and architecture, stating:

Some Beaux-Arts problems, among them the question of how to use the past, may perhaps be seen now as possibilities that are liberating rather than constraining. A more detached view of architecture as it was understood in the nineteenth century might also provoke a more rigorous critique of philosophical assumptions underlying the architecture of our own time. Now that modern experience so often contradicts modern faith, we would be well advised to reexamine our architectural priorities. (3)

The existential anxiety brought on by this exhibition was palpable in the architectural press and architecture community. While some attendees supposedly wore "Bring Back the Bauhaus" buttons (designed by Suzanne Stephens and Susana Torre) to the opening reception, others saw this exhibition as vindication of Venturi and other proto-Postmodernists—history and historic architecture was, could, and should be an inspiration and sourcebook for new architecture.(4) The exhibition, in addition to laying bare existing anxieties within American architecture, provided some legitimation to strains of design that were diverging from and/or reacting against Modernism. Not to mention examples of unabashed historicism such as the Getty Villa (Langdon & Wilson, 1970-75) in Los Angeles.

Enduring Legacies of Kahn & Johnson

The influence of Louis Kahn (1901-1974) loomed large over the 1970s, despite his premature death. Several of Kahn's most important U.S. projects were completed in the 1970s—including the Phillips Exeter Academy Library and Dining Hall (1965-72), the Kimbell Art Museum (1966-72), and the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven (1969-74)—and several others were under construction by the 1970s and completed later. As a professor at Yale from 1947-57, he had also taught a generation of architects who were coming into maturity in the 1970s. Kahn arguably provided some common ground for Modernists and proto-Postmodernists, and, at the least, garnered respect from both ends of the spectrum. Kahn’s work was specifically called out for praise in Drexler's catalog for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition Transformations in Modern Architecture (1979) and Jencks dubbed Kahn's Salk Institute—considered by some to be within the canon of Modernism—to, in fact, be “one of the first cosmic landscapes of Postmodernism."(5)

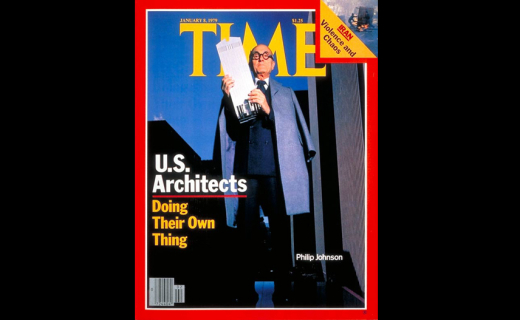

Philip Johnson, despite his credentials within the Modern canon (Seagram Building, Glass House, International Style exhibition at MoMA), pivoted to Postmodernism in the 1970s—proving his ability to take on and push forward various architectural styles as the prevailing winds shifted. Major works by Johnson in the 1970s included the Johnson building addition to Boston Public Library (1972)—a case study in contextual design with a Kahn-ian approach to geometry—the IDS Center, Minneapolis (1973) and Pennzoil Place, Houston (1970-76)—both of which exemplify a Late Modernist use of mirrored glass curtain walls. Johnson was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1979 and in the same year was one of the few architects ever to be featured on the cover of TIME magazine, where he is pictured holding a model of his seminal Postmodern work—the AT&T Building (550 Madison, NYC, 1978-84).

New Players On the Scene

While many prominent architects of the Modern Movement were reaching the end or late stages of their careers, other major players in the 1970s included architects who were trained in the Modernist school of thought and either continued within this strain—while pushing its bounds—or diverged entirely, and sometimes both. Architects like Paul Rudolph, John Portman, William Pereira, I.M. Pei, and larger firms such as SOM, HOK, and Gruen Associates, continued to produce influential work in the 1970s—generally working on large-scale commercial and institutional projects, and in some cases beginning to expand into massive projects abroad, particularly in the Middle East and Asia toward the end of the decade. Architects who were becoming more prominent during the 1970s included Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Charles Moore, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo (successors to Eero Saarinen’s firm upon his death in 1961), Cesar Pelli, Michael Graves, Robert A. M. Stern, Peter Eisenman, Richard Meier, Stanley Tigerman and Margret McCurry, Charles Gwathmey, and Frank Gehry, among many others. As these architects were coming into maturity in the 1970s, they were experimenting with various continuations and divergences from Modernism, and developing the material, formal, and linguistic framework that would shape the profession through the remainder of the twentieth century.

Whites vs. Grays

The exhibition and publication Five Architects (1972, reprinted 1975) was born out of several meetings hosted at MoMA of the Committee of Architects for the Study of the Environment (CASE)—first in 1969 and again in 1971—and featured the work of Eisenman, Graves, Gwathmey, Hejduk, and Meier, who would become known as the "New York Five" (a play on the earlier Modernist “Harvard Five” of the 1940s) or the "Whites." The Whites moniker referred to the architects’ proclivity for white exterior facades, the vein of Corbusier's villas, and the white cardboard architectural models that they presented. While this publication helped launch the careers of these architects into the mainstream of the architectural press, the Whites were not without their opponents and detractors. As architectural historian Leland M. Roth has observed,

Responding to this exhibition, and arraying themselves against the Whites were another group of young architects, whose spokesman, Robert Stern, call the ‘Grays.’ They believed that architecture, although a formal expression, works best when it acknowledges its context and incorporates allusions to the past, even references that are humorous and ironic. Both groups stemmed from Louis Kahn, but whereas the Whites moved sharply in the direction of Le Corbusier in the 1920s, toward abstraction, the Grays followed the trail blazed by Venturi.(6)

The Grays would become generally associated with Venturi, Moore, Stern, and architectural historian Vincent Scully (and Graves, who switched camps), and “new Classical” architecture, proto-Postmodernism, and vernacular architecture. The two camps represented two strains or directions in architecture in the 1970s that had numerous subcurrents, off-shoots, and responses. One such response came out of Los Angeles in a series of conferences hosted by Tim Vreeland, an architect teaching at UCLA, that featured architects such as Cesar Pelli, Anthony Lumsden, Eugene Kupper, Paul Kennon, and Frank Dimster, who dubbed themselves the “Silvers” in reference to their sleek, high tech approach to Late Modern design.(7)

Chicago Seven

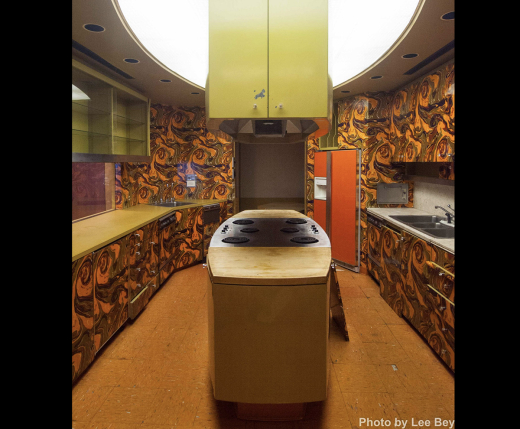

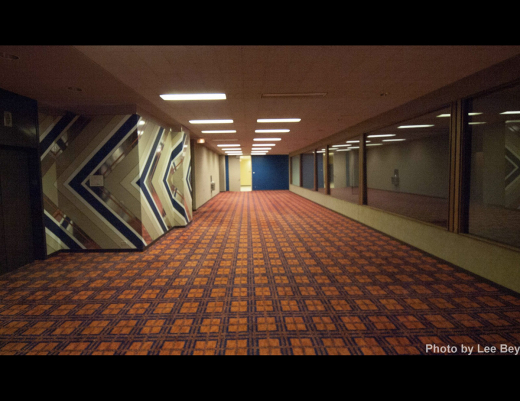

Although not a direct response to the Whites vs. Grays—the “Chicago Seven” arose in a parallel debate within architecture in the Midwest. Initially formed in protest against an exhibition One Hundred Years of Architecture in Chicago (1967), the group—which included Stanley Tigerman, Larry Booth, Stuart Cohen, Ben Weese, James Ingo Freed, Tom Beeby and James L. Nagle—criticized what they observed as a distorted over-emphasis on the role of Mies and his predecessors. Nagle observed, "It wasn't Mies that got boring. It was the copiers that got boring, ... You got off an airplane in the 1970s, and you didn't know where you were." That being said, fantastic examples of Late Modernist design within the Miesian tradition were still being constructed in the 1970s, but were still very much informed by their contemporary moment, particularly at the interiors. A great example is John W. Moutoussamy’s design for the Johnson Publishing Company—a Black-owned publishing company whose empire would include Ebony and Jet magazines—headquarters in Chicago in the early 1970s. Moutoussamy, an African American architect who had studied under Mies, designed a highly geometric and well-proportioned concrete, glass, and marble building, which featured lavish interiors, including the famous Ebony test kitchen, with the bold colors, patterns, and textures we have come to associated with 1970s interior design—which were done by Arthur Elrod and William Raiser under the direction of Eunice Johnson (Ebony fashion director and wife of the publishing company founder, John H. Johnson).

Charles Moore, Sea Ranch and the Third Bay Tradition

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, the Sea Ranch was making waves in the design community with early architectural designs in the 60s by Charles Moore and Donlyn Lyndon, William Turnbull, and Richard Whitaker (MLTW), Joseph Esherick, landscape architecture by Lawrence Halprin, and supergraphics by Bobbie Stauffacher Solomon. Sea Ranch was predicated on a concept of "living lightly on the land" which included use of local materials and also unabashedly took inspiration from regional vernacular architecture such as wood barns and mining structures. Although physically isolated on the windswept coast of Northern California, a four-hour winding drive from San Francisco, the Sea Ranch project was published widely and the "Third Bay Tradition" of architecture in the Bay Area would become highly influential in the 70s and on. The material and formal vocabulary of Sea Ranch was primarily utilized in residential design, but was not limited to rural or suburban single-family houses, and many examples can be seen in both urban and suburban multi-family housing—some of the most exceptional being by the likes of Beverly Willis and Fisher-Friedman Associates. Willis, whose previous work had included the Union Street Stores in San Francisco (1963) which was an early and influential modern prototype for adaptive reuse of historic buildings, developed a proprietary program known as Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis (CARLA) in 1970 which took a technological approach to residential siting while still embracing local traditions of material and form.

LA School

Moore’s influence was also felt in the burgeoning "Santa Monica School" or "Los Angeles School" in Southern California, particularly after Moore began teaching at UCLA (1975-1982) and formed Moore Ruble Yudell Architects & Planners in 1977. Other architects identified within the Los Angeles School gained traction in the 1970s, becoming more prolific in the 80s and 90s, included Morphosis (founded by Thom Mayne, James Stafford, and Michael Rotondi), Eric Owen Moss Architects, and Frank O. Gehry. The 70s buildings by these architects—such as Gehry's own Santa Monica residence (1978), Morphosis's 2-4-6-8 House in Venice (1978), and the Vista Del Mar Triplex by Moss (1976)—were primarily adventurous residential projects that explored more off-the-shelf materials, an ad-hoc, eclectic, or "incongruous" approach, and vibrant splashes of color—in some cases, foreshadowing Deconstructivism. The so-called LA School would continue to operate at the cutting-edge of architecture on the West Coast throughout the following decades. And Moore’s own work moved increasingly into the realm of classicist Postmodernism in the late 70s with projects like the Piazza d’Italia (1978) in New Orleans.

Minority and Woman Architects

Unfortunately, it is unsurprising that the architects, theorists, and "schools" whose work dominated architectural competitions and awards and graced the covers of establishment architecture periodicals in the 1970s were by-and-large white men. However, the profession was seeing a shift in the 70s as more women, African American and other minority students were enrolling in architecture programs and becoming licensed architects. The political movements in the 1960s striving for equality and civil rights resulted in integration of graduate and professional programs and more conscious efforts to grant opportunities to women- and minority-owned businesses in public projects, which opened the possibilities for a more diverse profession (although the profession, to this day, continues to suffer from a severe lack of diversity).

In 1971, the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) was founded by twelve African American architects—William Brown, Leroy Campbell, Wendell Campbell, John S. Chase, James C. Dodd, Kenneth B. Groggs, Nelson Harris, Jeh Johnson, E.H. McDowell, Robert J. Nash, Harold Williams, and Robert Wilson—who met at the annual AIA National Convention in Detroit that year. NOMA, whose mission as currently stated is "rooted in a rich legacy of activism, is to empower our local chapters and membership to foster justice and equity in communities of color through outreach, community advocacy, professional development and design excellence," has chapters across the country, including many affiliated student organizations at architecture schools.(9)

The 1974 Women in Architecture Symposium was held at Washington University in St. Louis, focused on challenges faced by women in the male-dominated profession, garnered national media attention, and inspired other symposia, events, and discussions in cities and institutions across the country. A 1977 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, Women in Architecture, organized by architect Susana Torre, was featured in Progressive Architecture (March 1977) and was accompanied by the publication Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective. Although women, African American, and other minority architects made strides in the 1970s, their names and work still remained less celebrated in the mainstream architectural press, especially at a national level, and thus local research and oral histories with living architects will be needed to supplement other research methods in order to piece together a full picture of architecture in the 1970s. Indeed it is only recently, that the profession has begun to better recognize the work of architects such as Denise Scott Brown (whose contributions were previously overlooked and credited only to Venturi, her husband and design partner) and Norma Merrick Sklarek (the first African American woman elected as a fellow of the American Institute of Architects and whose work is often attributed only to the large firms at which she was employed—Gruen and Associates and Welton Becket Associates).(10)

Conclusion

1970s architecture is in what curator and critic Mimi Zeiger has called the “ugly valley”—the bottom of the ever-revolving cycles of taste—and already we have seen the loss of notable examples of 70s architecture. However, like with Modernist architecture before and Victorian architecture before that, there will likely be a broader appreciation of the aesthetics of 1970s architecture over the next decade or so—but not without effort. We have already seen this struggle around Brutalist architecture, which has a wider cult following thanks to social media and photography, but still is widely under threat and not valued by all. Design and planning of the 70s is yet understudied, and numerous avenues of research await, particularly at the local and regional levels. °®¶¹app, along with other architects, architectural historians, advocates, and local community members, will be at the front lines of establishing both an understanding and appreciation of 1970s architecture in the years to come.

Sources

(1) Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1966, 1977, 2002).

(2) Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 17.

(3) Arthur Drexler, “Preface,” in The Architecture of the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts, catalog for an exhibition presented at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (October 29, 1975-January 4, 1976).

(4) In an interesting further twist, Torre’s own work became increasingly Postmodern and Stephens, an architecture critic, would go on to favorably review works by Stern and the like.

(5) Charles Jencks, The Story of Post-Modern Architecture: Five Decades of the Ironic, Iconic and Critical in Architecture (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 9.

(6) Leland M. Roth, American Architecture: A History (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001), 489.

(7) Daniel Paul, SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement: Late Modern, 1966-1990, prepared for City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources (July 2020).

(8) Daniel Paul, SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement: Postmodernism, 1965-1991, prepared for City of Los Angeles, Department of City Planning, Office of Historic Resources (July 2018).

(9) “About,” National Organization of Minority Architects, accessed August 3, 2020, .

(10) The “Pioneering Women of Architecture” initiative by the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation is a great resource with a growing repository of information, see .

(11) “Escape from Ugly Valley: A Conversation on Time and Taste,” conference session moderated by Mimi Zeiger, Preserving the Recent Past 3 (PRP3), Los Angeles, California, March 13-16. .

About

Hannah Lise Simonson received her Master's of Science in Historic Preservation at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture in 2017. Her thesis "Modern Diamond Heights: Dwell-ification and the Challenges of Preserving Modernist, Redevelopment Resources in Diamond Heights, San Francisco," was awarded the Outstanding Thesis in Historic Preservation by the UT Austin School of Architecture. She is currently an Architectural Historian & Cultural Resources Planner at Page & Turnbull in downtown San Francisco. She also serves as the President of the °®¶¹app/Northern California (NOCA) chapter and as a member of the Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project's Advisory Committee.