This essay was first submitted for the Fall 2021 seminar Architectural Strategies Against Consumerism at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and subsequently published in the seminar publication Against Throwaway Architecture: Design Strategies Against Consumerism. Revisions have been made for this submission to Docmomo US.

Rushed design processes, poor construction quality, post-occupancy mismanagement and a general lack of maintenance characterize the typical modernist public housing estate; their decline symbolic of the cycle of neighborhood obsolescence and redevelopment that once enabled these projects. While originally conceived as alternatives to blighted post-war urban neighborhoods, these stigma-prone estates throughout Europe and the Americas have ironically become convenient targets for demolition. It is no surprise that proponents for their preservation are first confronted with poor public perception and ideological conflicts – fundamental issues that are often more inhibiting than the physical viability of preservation. Afterall, we are reminded by Stephen Cairns and Jane M. Jacobs in Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture (2014) that the concept of obsolescence is not simply a categorically factual state, but a value judgement based on relative comparisons of context, ideology, and circumstance. Attempts to rehabilitate such stigmatized fabric are therefore obliged to negotiate between the ideals of preservation principles and socio-political pressure prioritizing a ‘rebranding.’ This essay evaluates two diverging approaches of building rehabilitation where the ultimate aim is to restore value within existing fabric.

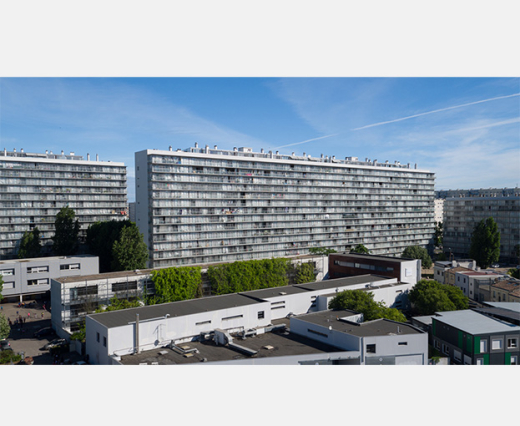

The first is Lacaton & Vassal’s 2016 transformation of Cité du Grand Parc in Bordeaux, a French Grand Ensembles (large-scale social housing complex) originally designed by Jean Royer and Claude Leloup in the 1960s. Here, the architects resisted state-endorsed demolition efforts by the total renewal of building envelopes, resulting in an image refresh that has afforded the buildings new value. Spridd’s Fittja People’s Palace, also completed in 2016 in the troubled Stockholm suburb of Fittja, is presented as the anti-thesis. There, the architects successfully preserved existing housing stock designed by Höjer & Ljungqvist in the 1970s by recasting a building as cultural artifact worth preserving (Otero-Pailos, Langdalen and Arrhenius 2016). Public mindsets are rehabilitated, ultimately negating disruptive construction work. In both cases, the immense pressure to erase these stigmatized housing blocks is surmounted by strategies that attempt to correct public perception. Functional remedies, while no less important to the success of the project, play secondary roles. Contextual underpinnings are critical to their diverging approaches and are key in the evaluation of either project.

In France, urban renewal is employed as a major tool in the national housing policy. For decades, redevelopment has been seen as the solution to eradicating urban ghettos and promoting social diversity. Demolition is often state-financed and supported by the Agence Nationale pour la Rénovation Urbaine (National Agency for Urban Renewal), while rebuilding is sponsored by social landlords and communes with attractive financing schemes (Aernouts, Maranghi and Ryckewaert 2020). Once products of post-war urban renewal schemes, French social housing complexes are now subject to a wave of redevelopment that seeks to diversify neighborhood social compositions and return to ‘traditional’ urban forms. As a result, residents have been confronted with multiple waves of eviction and relocation due to cascading cycles of redevelopment, regularly losing their established ways of living and familial connections. Even as redevelopment seeks to abolish these symbols of urban decay and restore social housing to the scale of the historic French city, their contemporary replacements are criticized as failing to generate improved social constructs (Aernouts, Maranghi and Ryckewaert 2020). Here, the Grands Ensembles are often exploited as scapegoats for flawed social policy while their demolition is instrumentalized as political tools to promote progress.

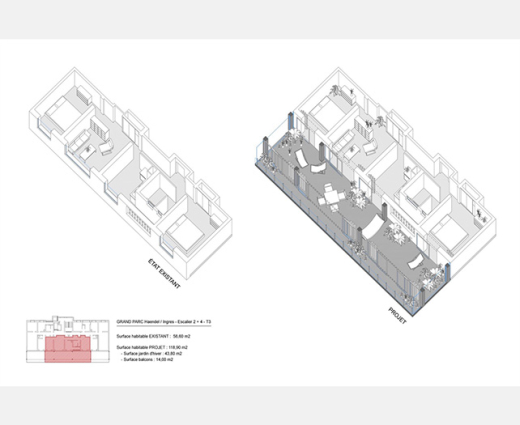

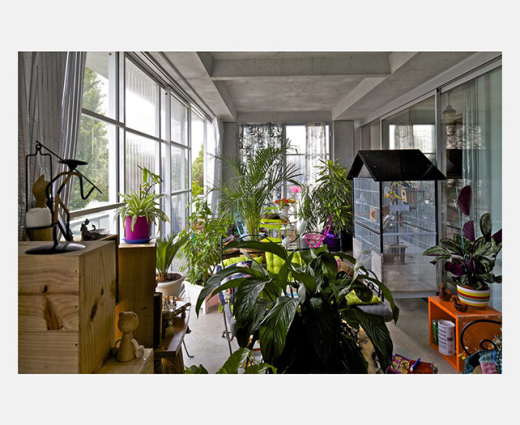

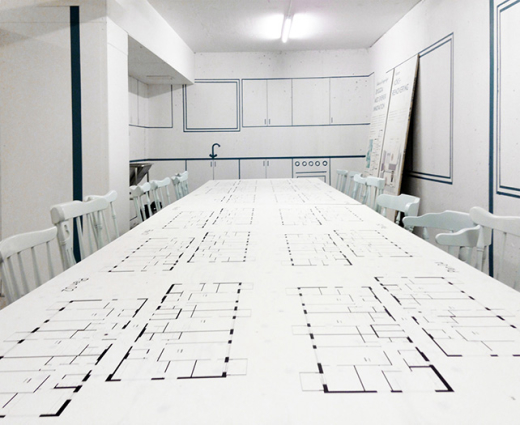

Lamenting the state’s intention to demolish many housing blocks, Lacaton & Vassal developed PLUS, a study that envisioned adding to and renovating existing housing stock, thereby allowing for their conservation. Their manifesto was subsequently piloted in Paris and Saint-Nazaire. Additions consisting of balconies and winter gardens were added to the exteriors, enlarging habitable space, and rehabilitating the buildings’ image. These projects attracted the attention of Aquitanis – Bordeaux’s social housing association. Lacaton & Vassal were invited to perform a rehabilitation of three social housing blocks in Cité du Grand Parc, a development typical of 1960s French mass housing projects. Fortunately, demolition of the three blocks had already been ruled out prior to Lacaton & Vassal’s commission, giving the architects liberty to replicate a similar process as had been executed in prior work.