The Reynolds Metals Company capitalized on the persuasive power of aluminum, by re-inventing it in such popular post-war campaigns as “The House of Ease,” and “Do-It-Yourself!” [1] After serving as a key material for World War II aircraft frames and ship infrastructures, Reynolds Metals aluminum was re-cast from military to domestic use. Aluminum’s versatility enabled it to take on a multitude of colors, forms, textures, and effects. These qualities made it, in the words of David Reynolds, company vice president in charge of sales, “the greatest salesman of all.”[2]

In 1945, the company pioneered aluminum siding for homes and buildings and in 1947, created what would become its hallmark product, Reynolds Wrap. With Reynolds Wrap, the corporation discovered aluminum’s best use in its as wrapping potential. As we will see in this essay, wrapping would extend to architecture, as a literal metaphor for the separation of form from structure, thus signaling a re-evaluation of modernism. As a non-structural architectural material, aluminum offered communicative properties of symbolism and expression. This essay will discuss the Reynolds Metals regional headquarters as a “new formalist” expression, which evolved beyond corporate modernism.

By the mid-1950s, Reynolds Metals’ Company had launched an advertising campaign directed at a new target— the building industry. The campaign included the commissioning of Aluminum in Modern Architecture, a 1956 two-volume book that highlighted 100 examples of aluminum in building since World War II. In it were conversations about the potential of aluminum use in modern architecture with a long list of influential architects including Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Commissioning an architectural showcase for aluminum would be the next step in Reynolds’ ambitious post-war business plan.

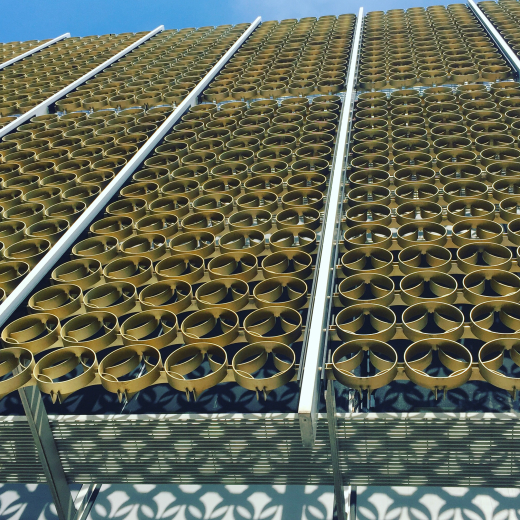

In 1956, Reynolds hired Troy, Michigan-based architect, Minoru Yamasaki to design their regional sales headquarters in Southfield, a suburb of Detroit. The site selection was strategic, as the client sought close proximity to “the technological center of the country,” where the headquarters of General Motors, Ford and Chrysler were located. While Reynolds marketed aluminum to the building industry, they also directed their interests at the booming automobile industry. Aluminum producers in the mid-1950s had supplied the auto industry with only small parts, but they had long hoped to capture a larger share of Detroit’s big-volume metals business. Reynolds’ strategy was to thrust aluminum into the view of Detroit automakers with a new regional headquarters building.