By: Charlene Roise, President, Hess, Roise and Company, Historical Consultants, Minneapolis MN

By: Charlene Roise, President, Hess, Roise and Company, Historical Consultants, Minneapolis MN

Marcel Breuer and Associates had a unique opportunity in the 1960s when hired by the to design the Third Powerplant at Grand Coulee, a massive irrigation and hydroelectric project straddling the Columbia River near Spokane, Washington. The resulting structure is a significant design statement of the era, admirably displaying both the solid strength of reinforced concrete and the expressive forms that it can produce.

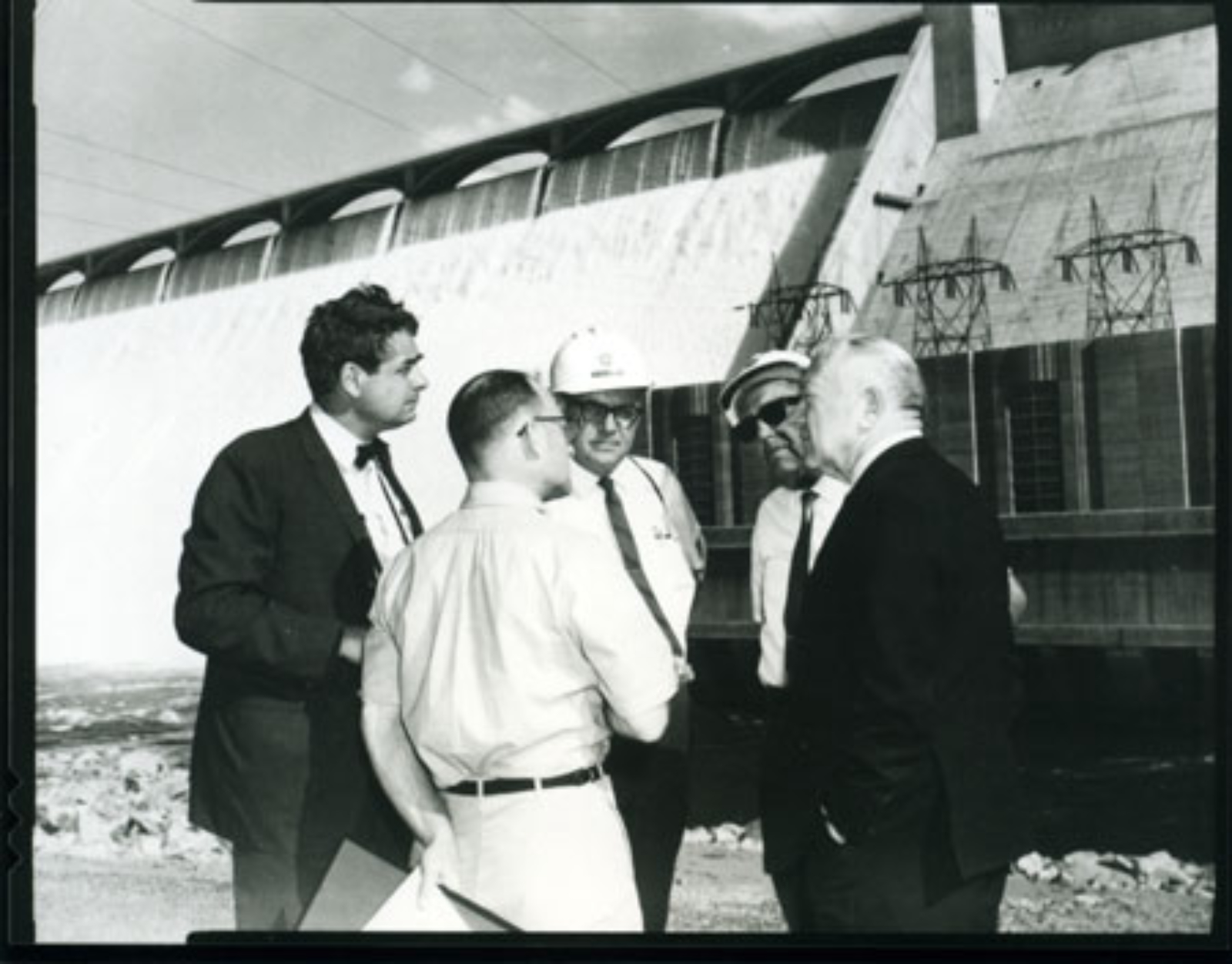

Photo (left): Photographic copy of photograph, H. S. Holmes, photographer, June 27, 1968 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington). “Discussing the architectural design of the Third Powerplant and surrounding area from left are: Mr. Hamilton Smith, Marcel Breuer Associates, New York; Mr. Kenneth Brooks, Spokane Architect; Mr. Harold Arthur, Denver USBR Office; Mr. Otis Peterson, Assistant to the Commissioner-Information, Washington, D.C.; and Mr. Marcel Breuer, Architect, New York.”

The Columbia Basin Project was launched by Reclamation in the 1930s after decades of planning. Grand Coulee is the largest of a series of dams that impound water to irrigate arid but fertile farmland in eastern Washington State. The dams also harness the river’s power to generate electricity, reduce flooding, and produce recreational opportunities.

Creating work for hundreds of laborers during the Great Depression, construction at Grand Coulee focused first on the generating facility on the river’s west side (Left Powerplant), with work on a companion on the other bank (Right Powerplant) starting soon thereafter. A third powerhouse had been anticipated in the overall plan, and operation of the first two plants had barely become routine by 1952 when Reclamation began exploring possible sites for another plant. Implementation, though, was delayed for more than a decade by political and economic issues.

Creating work for hundreds of laborers during the Great Depression, construction at Grand Coulee focused first on the generating facility on the river’s west side (Left Powerplant), with work on a companion on the other bank (Right Powerplant) starting soon thereafter. A third powerhouse had been anticipated in the overall plan, and operation of the first two plants had barely become routine by 1952 when Reclamation began exploring possible sites for another plant. Implementation, though, was delayed for more than a decade by political and economic issues.

Photo (right): General view of Grand Coulee Dam and town of Coulee Dam from Crown Point vista. View to south. The Third Powerplant is at the left end of the dam complex.

The project finally gained momentum by the mid-1960s as Reclamation sought to reduce the amount of water spilling over the dam, the demand for power grew in the Northwest, and the continent’s power grids were interconnected. Thanks to improvements in hydroelectric technology, the anticipated capacity of the new plant had grown to nearly twice that of either of the existing plants. With power from the twelve 600-megawatt units ultimately added to the existing units, Grand Coulee’s capacity would be over 9,000 megawatts, larger than any power facility in the world. Electrical World remarked that the Third Powerplant alone “exceeds the total capacity of all 50 power plants the Bureau has constructed.”1

The project’s large scale was also justified by Cold War sparring. In addition to being stung by the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the United States had lost bragging rights to the world’s largest hydroelectric facility two years earlier when the Soviets completed the 2.3-megawatt Kuibyshev Powerplant on the Volga River. With more Soviet plants on line by 1958, Grand Coulee sank to the fifth largest. The Third Powerplant would redeem the United States’ top rank.2

Reclamation’s in-house engineers had designed the first two plants, which put function before aesthetics. The project’s details and massing reflected the Streamline Moderne style that was popular at the time, but the design was understated. The Third Powerplant was to break from this mold. “With the design, construction, and operation of the Third Powerhouse, the Grand Coulee Dam complex will achieve new magnitude in the public mind,” a Reclamation report explained. The prominence of this exceptional engineering feat deserved an exceptional design, so Reclamation turned to , one of the major architects of the mid-twentieth century.3

Reclamation’s in-house engineers had designed the first two plants, which put function before aesthetics. The project’s details and massing reflected the Streamline Moderne style that was popular at the time, but the design was understated. The Third Powerplant was to break from this mold. “With the design, construction, and operation of the Third Powerhouse, the Grand Coulee Dam complex will achieve new magnitude in the public mind,” a Reclamation report explained. The prominence of this exceptional engineering feat deserved an exceptional design, so Reclamation turned to , one of the major architects of the mid-twentieth century.3

Photo: Photographic copy of photograph, H. S. Holmes, photographer, August 28, 1974 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington). “Aerial view looking east. Tailrace, Powerhouse, Penstocks and Forebay Dam. Specs. No. DC-6790 Contr. Vinnell-Dravo-Lockheed-Mannix.”

Born in Hungary in 1902, Breuer was educated and taught at the Bauhaus before relocating to London in the mid-1930s and the United States in 1937. By the 1950s, after a number of years on the architecture faculty at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Breuer devoted himself to private practice and established a thriving international business based in New York City. His clients included the United States government, for which he designed an embassy in The Hague and new headquarters for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, both in Washington, D.C.4

is particularly noteworthy in relation to Breuer’s work at Grand Coulee. HUD’s creation in 1965 marked a significant change in federal housing policy, and this innovation merited an equally groundbreaking headquarters. Erected in 1966–1968, the HUD Building represented an early use of precast concrete for a federal building. In addition to being economical, coming in millions of dollars under budget, it was considered an aesthetic success. Aesthetics had come to play a more important role in federal construction after President Kennedy issued addressed to the heads of federal agencies, in 1962. The principals were first outlined in an essay by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was assistant secretary of labor at the time. The beautification campaign was subsequently taken up by Lady Bird Johnson, who also became involved in environmental causes, including opposition to Reclamation’s plans for dams in the Grand Canyon.5

This tangle likely motivated Reclamation to appoint a Board of Artistic Consultants in 1967 to provide advice on design issues for major projects. Reclamation Commissioner Floyd Dominy “enlist[ed] members of national repute,” and the board soon set to work. “I was delighted, but not too surprised, when the board came back from a survey trip to assert that many of our dams were things of sculptured beauty,” he reflected. “But they added that some appurtenant structures and surroundings left something to be desired. We took them at their word and have contracted with Marcel Breuer and Associates of New York to furnish architectural concepts for our biggest single job now underway.”6

Progressive Architecture lauded Reclamation’s decision to retain Breuer as “an action believed to be without precedent.” The formal relationship apparently began in September 1967 when Reclamation staff visited Breuer’s Manhattan office to negotiate a contract. Tician Papachristou, an architect on Breuer’s staff, wrote a letter to Reclamation the following week summarizing what had been discussed, adding: “Mr. Breuer has asked me to convey to you again his strong personal interest in this commission.” The scope of work included “the design of all visible parts of the proposed construction, including the Forebay Dam, the Third Power Plant, visitors’ facilities, etc., with particular attention to color, form, surface, choice of materials and lighting.” Papachristou continued: “Generally, we see our office as an instrument at your disposal to provide necessary consultations in questions of architectural or aesthetic nature. . . . We assume, of course, that all engineering will be provided by you.” A later article in Architectural Record summarized the relationship: “Working with the 450-man A/E staff at the Bureau’s Engineering & Research Center in Denver, Breuer’s office . . . strove to give this massive and highly complex project a visual harmony with its setting and a sensitivity to user need.”7

Progressive Architecture lauded Reclamation’s decision to retain Breuer as “an action believed to be without precedent.” The formal relationship apparently began in September 1967 when Reclamation staff visited Breuer’s Manhattan office to negotiate a contract. Tician Papachristou, an architect on Breuer’s staff, wrote a letter to Reclamation the following week summarizing what had been discussed, adding: “Mr. Breuer has asked me to convey to you again his strong personal interest in this commission.” The scope of work included “the design of all visible parts of the proposed construction, including the Forebay Dam, the Third Power Plant, visitors’ facilities, etc., with particular attention to color, form, surface, choice of materials and lighting.” Papachristou continued: “Generally, we see our office as an instrument at your disposal to provide necessary consultations in questions of architectural or aesthetic nature. . . . We assume, of course, that all engineering will be provided by you.” A later article in Architectural Record summarized the relationship: “Working with the 450-man A/E staff at the Bureau’s Engineering & Research Center in Denver, Breuer’s office . . . strove to give this massive and highly complex project a visual harmony with its setting and a sensitivity to user need.”7

Photo (above): General view of Third Powerplant and Forebay Dam. View to southeast.

With the hope of issuing the prime construction contract in June 1969, Reclamation wanted plans ready in 130 days—a lightning-fast turnaround of just over four months. Breuer’s office, however, estimated that the process would take seventeen to twenty months. They ultimately agreed that conceptual studies and preliminary design development would be done within 180 calendar days of the contract award, with final plans and specifications finished 110 calendar days later.8

Hamilton P. Smith served as Breuer’s partner in charge, with Thomas Hayes as associate architect. Paul Weidlinger was the structural consultant. A few years earlier, Smith had overseen the design of the in New York, which opened in 1966. The Whitney was greeted with generally positive reactions, although some balked at its uncompromising modernism. Another Breuer project a few years later, around the time the firm was hired for the Grand Coulee project, was more universally criticized—a tower atop New York’s Grand Central Terminal. A second version, which replaced the station’s facade, was considered even less acceptable. The Grand Central battles eroded some of the enthusiasm that architecture critics and the public felt for Breuer. Hence, the Grand Coulee design dates from the apex of Breuer’s career.9

The concept design was well along by December 1968 when Progressive Architecture published a small, preliminary drawing of the plant: “Features of the Breuer concept, which may still be modified before construction, include an inclined elevator, a glass-enclosed cab moving up and down the face of the dam’s 475'-high penstocks. The elevator will stop midway along the incline to give visitors access to a platform cantilevered out of the rock cliff supporting the Forebay Dam, where a cross-over bridge spanning the transformer deck will lead to the powerplant. Visitors will enter the generator hall of the powerplant at a level above that of the bridge crane, and will be able to cross the gallery at this level to a balcony from which they may view the powerplants, the spillway, and the Columbia River itself.” Visitors could also ride to the bottom of the elevator shaft to see the turbines up close.10

The concept design was well along by December 1968 when Progressive Architecture published a small, preliminary drawing of the plant: “Features of the Breuer concept, which may still be modified before construction, include an inclined elevator, a glass-enclosed cab moving up and down the face of the dam’s 475'-high penstocks. The elevator will stop midway along the incline to give visitors access to a platform cantilevered out of the rock cliff supporting the Forebay Dam, where a cross-over bridge spanning the transformer deck will lead to the powerplant. Visitors will enter the generator hall of the powerplant at a level above that of the bridge crane, and will be able to cross the gallery at this level to a balcony from which they may view the powerplants, the spillway, and the Columbia River itself.” Visitors could also ride to the bottom of the elevator shaft to see the turbines up close.10

Photo (above): Photographic copy of construction drawing, Bureau of Reclamation, November 1, 1976 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington). “Grand Coulee Dam: Forebay Dam and Third Power Plant – Elevations and Sections.”

Preliminary site work for the project had begun in January 1967, months before Reclamation contacted Breuer. A joint venture, Vinnell-Dravo-Lockheed-Mannix (VDLM), won the prime construction contract in 1970. Totaling $112.5 million, this was the largest single contract that Reclamation had ever awarded. By August 1972, Engineering News-Record reported: “Ironworkers are just now getting to the really difficult rebar placement—the building’s folded, stiffened concrete walls, designed by New York City architect Marcel Breuer and Associates, to provide ‘continuity, visual interaction and structural integration’ with the dam.” In addition, “the 84-ft-high walls must be capable of supporting a pair of 275-ton bridge cranes, so there’s a nightmare of ever-changing rebar configurations involved.” The concrete sections stood 85' tall and were from 12" to 54" thick.11

The prestressed, precast roof tees were fabricated by the Central Pre-Mix Concrete Company, which began producing them at its Spokane facility in May 1972. By September 15, the company had placed concrete for every roof tee. The first tee was delivered to Grand Coulee in July. By the end of the year, all 122 tees were at the jobsite and 14 were in position over the turbine erection bay. The remaining tees were stored nearby until needed. The last concrete was placed for the superstructure on January 18, 1974, and VDLM had completed “all precast concrete members for the powerplant structure . . . with placement for crossover bridge panels” in the following month.12

The prestressed, precast roof tees were fabricated by the Central Pre-Mix Concrete Company, which began producing them at its Spokane facility in May 1972. By September 15, the company had placed concrete for every roof tee. The first tee was delivered to Grand Coulee in July. By the end of the year, all 122 tees were at the jobsite and 14 were in position over the turbine erection bay. The remaining tees were stored nearby until needed. The last concrete was placed for the superstructure on January 18, 1974, and VDLM had completed “all precast concrete members for the powerplant structure . . . with placement for crossover bridge panels” in the following month.12

Photo (left): Photographic copy of photograph, Bob Isom, photographer, March 2, 1972 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington). “Lifting beam used to pick exterior form for Super Structure [sic]. Specs. No. DC-6790 Contr. Vinnell-Dravo-Lockheed-Mannix.”

The columns for the rails for the three overhead, traveling cranes were incorporated into the building’s concrete walls. There was also a 1,900-ton, self-propelled gantry crane that ran on steel tracks extending the entire length of the plant’s main floor. It was custom-designed by the R. A. Hanson Company, which used its initials for the name of the model: the RAHCO 2000T. Reclamation was well aware that the architectural quality of the powerplant could be undermined by an unsightly crane, so the bid documents had insisted that “care shall be used in the design of the gantry to produce a pleasing appearance.”13

The first turbine-generating unit in the Third Powerplant was started in August 1975. By the end of the year, the plant had produced nearly 1 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity. Three years later, the eye-catching cylindrical Visitors Center, also designed by Breuer’s office, opened on the opposite side of the river.14

Breuer’s striking Third Powerplant was one of the dominant features in this environment. Some have speculated that Breuer’s Brutalist design was influenced by Fort Peck Dam in Montana, particularly a construction shot taken by Margaret Bourke-White and featured in November 1936. Breuer himself, however, credited a much earlier source, describing the plant’s giant concrete form as having “dimensions truly Egyptian.” As one of his biographers observed, “Breuer had a deep interest in the monumental architecture of Egypt and its formal constructs—the ramps, the battered walls of the pylons, the flat-topped inclines of the low-lying mastabas, the trapezoidal masses of heavy stone, and the serial repetition of individual elements, all of which found their way into his work.”15

Breuer’s striking Third Powerplant was one of the dominant features in this environment. Some have speculated that Breuer’s Brutalist design was influenced by Fort Peck Dam in Montana, particularly a construction shot taken by Margaret Bourke-White and featured in November 1936. Breuer himself, however, credited a much earlier source, describing the plant’s giant concrete form as having “dimensions truly Egyptian.” As one of his biographers observed, “Breuer had a deep interest in the monumental architecture of Egypt and its formal constructs—the ramps, the battered walls of the pylons, the flat-topped inclines of the low-lying mastabas, the trapezoidal masses of heavy stone, and the serial repetition of individual elements, all of which found their way into his work.”15

Photo (right): Fort Peck Dam on cover of first issue of LIFE magazine, 1936.

Breuer was fascinated by the aesthetic potential of concrete: “I believe the architect can fully express himself as an artist by means of concrete.” He elaborated: “The greatest esthetic design potential in concrete . . . is found through interrupting the plane in such a way that sunlight and shadow will enhance its form, while through changing exposure a building will appear differently at various moments of the day.”16This potential was clearly achieved by the folded forms and textured surface of the Third Powerplant.

Breuer was also intrigued by the interior spaces created by massive concrete walls, finding spirituality in secular as well as religious structures. In an interview in 1979 about a recently completed project, the in Muskegon, Michigan, Breuer was asked how he “arrive[d] at the concept of a religious space, as opposed to an office space or an ordinary meeting hall.” He responded: “I have the feeling . . . that any space which is larger than necessary and higher than necessary, and in which the structure and the whole building of the space is visible, . . . that this space created is simply automatically religious.” Although not a religious man, he felt a sense of spirituality “in a big hydroelectrical power plant in Switzerland,” adding: “We have built a rather large one, the expansion of the Grand Coulee Dam. I have not seen it yet because I cannot travel much, but I think that this must also have this feeling. It is an enormous empty space carried by monumental concrete walls, folded. Everything is dustless and spotless, there is no daylight, only artificial light, there are no people, only the heads of twelve turbines visible, of which each produces enough electricity to operate the whole city of Denver.”17

Breuer’s health was failing by the time his office received the commission, and he was unable to visit the completed project before he died in 1981. The Third Powerplant opened in 1974.

Breuer’s health was failing by the time his office received the commission, and he was unable to visit the completed project before he died in 1981. The Third Powerplant opened in 1974.

The Third Powerplant is generally considered a masterpiece of modern design. As Breuer’s biographer Isabelle Hyman has noted, “Breuer and concrete construction came together with colossal force at the third power plant and forebay dam sited at Grand Coulee against the imposing backdrop of the Columbia River basin.” She added that four of his designs—Grand Coulee Dam, the Saint Francis de Sales Church, the Whitney, and the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Education Wing—“hold a significant place in American late modern architecture.”18

Photo (left): Transformer deck behind Third Powerplant. Walkway for visitors is above. View to west.

This article was excerpted from a Historic American Engineer Record documentation study (HAER No. WA-139-A) initiated by the Bureau of Reclamation’s Pacific Northwest Regional Office in Boise, Idaho. The study and this article were written by Charlene Roise, principal of Hess, Roise and Company, historical consultants based in Minneapolis, with research assistance from staff historian Elizabeth Gales and staff researcher Penny Petersen. Photographic documentation was completed by Clay Fraser, principal of Fraserdesign, Loveland, Colorado.

Additional HAER photographs are available at the end of this article.

Primary Sources

Breuer, Marcel. Papers. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (http://www.aaa.si.edu/collectionsonline/breumarc).

Nelson, Harold T. “Columbia Basin Project-Washington, Coulee Dam Field Division, Third Power Plant, Grand Coulee Dam.” Report. Boise. April 1953.

U.S. Department of the Interior. Bureau of Reclamation. Annual Project Histories. Columbia Basin Project.

———. Annual Project Histories. Construction Division-Grand Coulee Third Powerplant, Grand Coulee Dam Project Office-Columbia Basin Project.

———. Annual Project Histories. Grand Coulee Third Powerplant-Columbia Basin Project.

———. “Background for Studies Investigating Desirability of Enlarging the Third Powerplant at Ground Coulee Dam, Washington.” October 1975. At U.S. Bureau of Reclamation-Boise.

———. “Columbia Basin Project, Washington, Grand Coulee Dam Third Powerplant.” February 1954. At RG 115, Records of the Bureau of Reclamation, Engineering and Research Center, Project Reports, 1910-55, 8NN-115-019, Box 331, National Archives and Records Administration-Rocky Mountain Region, Denver.

———. Final Environmental Impact Statement for Columbia Basin Project in Adams, Douglas, Ferry, Franklin, Grant, Lincoln Okanogan and Walla Walla Counties. 1971.

———. “Third Powerplant, Columbia Basin Project, Washington: Definite Plan Report.” September 1967.

———. Third Powerplant Construction Engineer to Assistant Commissioner, Engineer and Research. Memorandum. August 25, 1978. At Powerplants and Equipment, Third Powerplant, Box 651, Bureau of Reclamation-Boise.

Secondary Sources

Arthur, Harold G. “Proposed Third Power Plant at Grand Coulee Dam.” Journal of the Power Division, Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers 93 (March 1967): 15-29.

Breuer, Marcel. Introduction to Living Architecture: Egyptian, by Jean-Louis de Cenival. London: Oldbourne Book Company Ltd., 1964.

“Breuer Power.” Architecture Plus 2 (May-June 1974): 126-127.

“Breuer Takes Gov’t. Dam Job.” Progressive Architecture 49 (April 1968): 66.

“Coulee Dam’s Third Powerplant Is a Study in Superlatives.” Engineering News-Record, August 24, 1972, 28-29.

“Dam Design by Breuer.” Progressive Architecture 49 (December 1968): 45.

“8,000,000 Kw. Goal of Columbia River Development.” Electrical West 72 (February 1934): 16-17.

Gould, Lewis L., ed., Lady Bird Johnson: Our Environmental First Lady (Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1999).

Hess, Sean C. “Documentation of a Finding of No Adverse Effects for the Third Power Plant Crane Controls Modification Project.” February 2010.

Howarth, Shirley Reiff. “Marcel Breuer: On Religious Architecture.” Art Journal 38 (Summer 1979): 257-260.

Hyman, Isabelle. Marcel Breuer, Architect: The Career and the Buildings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001.

Pie, Edgar A. “The Word from Washington.” Consulting Engineer, November 1968, 82.

Pitzer, Paul. Grand Coulee. Pullman, Wash. Washington State University Press, 1994.

“Power Station, Bureau of Reclamation.” Architectural Record 164 (December 1978): 126-127.

“The Star.” Typescript. At Grand Coulee Administration Building Library. December 1971.

Photo: Photographic copy of photograph, Bob Isom, photographer, November 15, 1976 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington). “Generator Erection Bay – Unit 22 Rotor Steel Stacking.”

Photo: North end of Third Powerplant. View to south.

Photo: Detail of V-shape buttresses on outside wall of Third Powerplant. View to southeast.

Photo: 2000-ton gantry crane inside Third Powerplant. View to north.

Photo: Stairwell and air intake on the main generator bay floor in Third Powerplant. View to southwest.

Photo: Detail of concrete ribbing on interior wall of Third Powerplant. M = main floor; el. 1012 = elevation 1012 feet above sea level. View to east.

Photo: Photographic copy of construction drawing, Bureau of Reclamation, October 1, 1971 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington).

Photo: Photographic copy of construction drawing, Bureau of Reclamation, October 1, 1971 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington).

“Grand Coulee Third Power Plant: General Arrangement – Longitudinal Sections thru Galleries.”

Photo: Photographic copy of construction drawing, Bureau of Reclamation, September 19, 1969 (original print located at Grand Coulee Power Office, Grand Coulee Dam, Washington).

“Grand Coulee Third Power Plant, Architectural: Special Concrete Finishes – Observation Balcony - Elevation and Section.”