As time goes on, the preservation community and society at large is not only recognizing the significance of Goldberg’s architecture, but coming to appreciate the aesthetic of exposed concrete architecture and embrace the narrative that modern concrete buildings can be significant and worth saving. Thus, when it comes to rehabilitation work to the exterior of Goldberg’s buildings, we now tend to value features of the architect’s original design, including the surface appearance. A building’s exterior surface, especially when it is expressed in one solid material (in this case concrete) is integral with the building’s design and often highly designed. Through researching Goldberg, his particular use of concrete, and his intentions for these buildings, clearly the surface of his structures was a highly significant feature of his buildings. Moving forward, a great effort should be made to retain what is left of the concrete surfaces of Goldberg’s works. In general, it does seem that more appropriate decisions are being made as evidenced by the recent and future work on River City.

About the Author

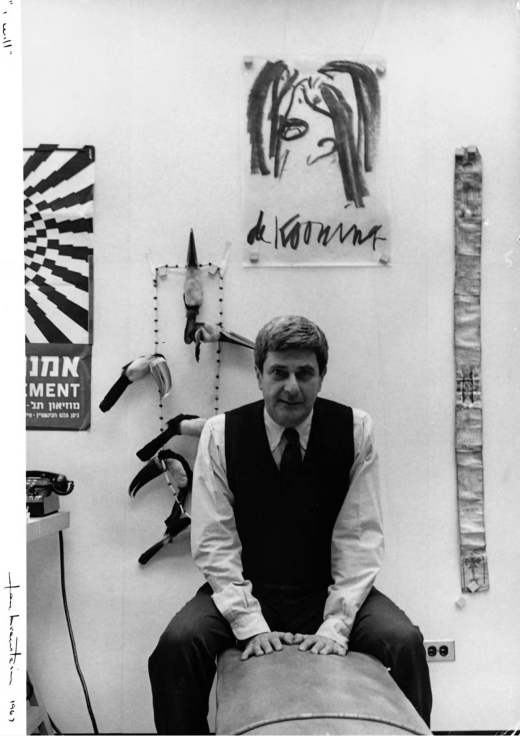

Andrea will be completing her MS in Historic Preservation this May from Columbia University and is being thoughtfully advised by Theodore Prudon. Prior to moving to New York, she graduated with a degree in architecture form the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana and worked in Chicago as a junior architect. Andrea is a pursuing a career as a preservation architect and currently works at Beyer Blinder Belle in New York City. She is also a current member of °®¶¹app.

Notes

[1] “Marina City-World’s Tallest: Apartment Buildings, Reinforced Concrete Buildings” Concrete Facts (Expanded Shale, Clay and Slate Institute, Vol. 8, No. 1), 2-3.

[2] Richard J. Kirby, “Fiberglass Forms – A Progress Report”, 1962, The Aberdeen Group.

[3] “The End is Coming: Marina City goes Condo,” The Biography of Chicago’s Marina City. http://www.marinacity.org/history/story/goes_condo.htm

[4] Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. “Investigation of the Exterior Concrete and Waterproofing on Marina Towers for the Marina Towers Condominium Association Chicago, Illinois” WJE NO. 881397 October 20, 1989. Source: Bertrand Goldberg Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Library at the Art Institute of Chicago, Series VI, Box 18, Folder 18.6 (accessed Thursday December 29, 2016).

[5] Duntemann, John and Brian Greve, “Marina City – The History and Restoration of an Iconic Façade,” IABSE Conference – Structural Engineering, Providing Solutions to Global Challenges, September 23-25 2015, Geneva, Switzerland.

[6] Betty J. Blum, Oral history of Bertrand Goldberg, interview (1993): 185.

[7] John W. and Heinrich Klotz, Conversations with Architects (New York: Praeger, 1973), 125.

[8] Carl W. Condit, Chicago, 1930-70: Building, Planning, and Urban Technology (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1974), 58.

[9] Spec section: Division D-4A Cast-in-place Concrete: 4A-09.5 Exposed-Finished Surfaces, source:

[10] John W. and Heinrich Klotz, Conversations with Architects (New York: Praeger, 1973), 143.

[11] Maya Dukmasova, “The Goldberg Variation: High-rise Public Housing That Works.” Chicago Reader, Nov. 5, 2016.

[12] Carol Dyson, email to author, December 1, 2016.

[13] Greene, Thom. Thom Greene to Mike Jackson and Carol Dyson Re: Hilliard Homes Exterior Concrete Finish, September 12, 2003. Letter. Courtesy of Greene & Proppe Design Inc., email from Thom Greene February 6, 2017.

[14] Betty J. Blum, Oral history of Bertrand Goldberg, interview (1993): 254.

[15] Geoffrey Goldberg. “Bertrand Goldberg: A Personal View of Architecture” Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives edited by Charles Waldheim and Katerina Ruedi Ray (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2005), 237.

[16] Specifications Section 03300 Structural Concrete: Section 13.2

[17] “River City II Project Meeting Minutes” June 26th, 1984 (Tuesday) 8:30AM; source: Bertrand Goldberg Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Library at the Art Institute of Chicago, Series VIII, Box 23, Folder 23.20.

[18] Cunov, Robert C, Bertrand Goldberg Associates, “Field Inspection Report” November 6, 1984, River City II; source: Bertrand Goldberg Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Library at the Art Institute of Chicago, Series VIII, Box 23, Folder 23.20.