Parking at Ala Moana Center can be a nightmare. Even for those of us that have been going there for decades, finding a store can be almost as challenging. As kids, we all knew where all the important things were: the sculptures to play on, the deli with the tasty sandwiches, the koi ponds, the hippie store with the imports from India, and the book/record store. It was a adventure to go into “town” to shop at the mall. Even after changes to Ala Moana in the early 80s, finding the cute shop with the funky international jewelry, or familiar “local” drug store or any of the three department stores was not tricky. Navigation was easy. On the lower level, almost all the shops (HOPACO and its glorious pens!) were located on the outer perimeter of the mall building. On the upper level, shops were all along the main open passageway, with a few accessible from the parking side, easy! The mall’s appearance now - muddled and confusing from all the years of updates, is an unfortunate result of its more than sixty years of success.

Ala Moana Center Re-rearranged

Author

Lesleigh Jones

Affiliation

°®¶¹app/Hawaii

Tags

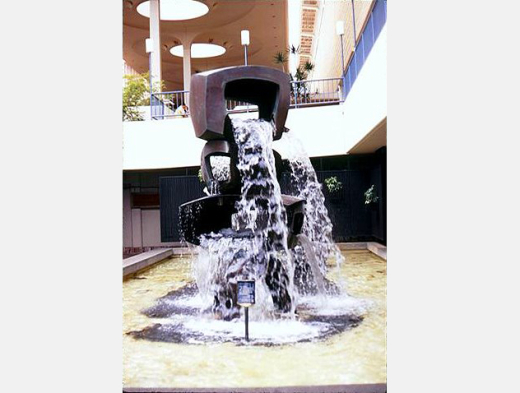

One goal of Ala Moana’s developer, Hawaiian Land Company, and its head Lowell Dillingham, was to fill the Center with a mix of local businesses, and ones with a history in the islands. Another was to provide a pleasant atmosphere compatible with the island setting. This meant an open-air design, landscaping, and artwork. John Graham and Company’s modern design for the buildings featured gently sloping roofs and wide overhanging eaves, with coral stone and breeze-block accents. The mall’s overall design was complemented by individual, architect-designed storefronts and interiors.

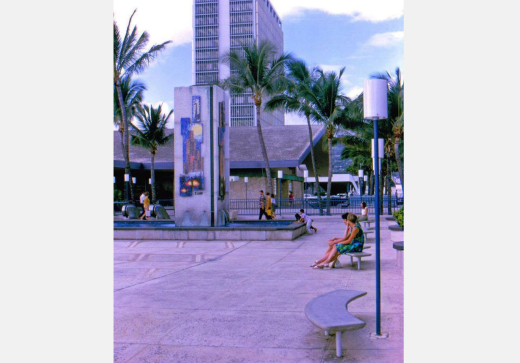

Landscaping designed by, or in collaboration with, Lowell Dillingham included planter boxes ringing the upper level between walkways and parking, with coconut trees extending from the lower level through “pukas” in the upper-level deck between planters. Planter boxes and benches were scattered along the inner passageways. Additional features included koi ponds that extended much the length of Phase II and an aviary. Two children’s play areas provided youngsters something to do while their parents shopped. Artwork by local artists, from as well known as “tiki” artist Edward Brownlee, and as unknown as Charles Wilson, Dillingham’s manager for the mall’s construction, was included. One of the play areas consisted of a sand box with large Brownlee sculptures meant to for children to climb on.

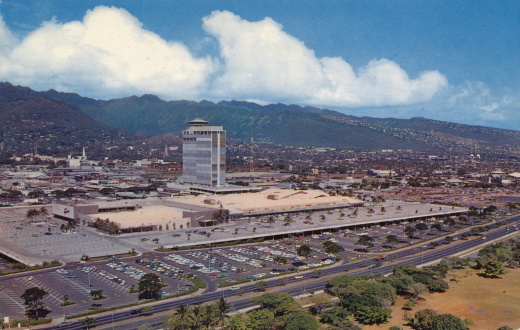

Ala Moana Center was such an immediate success after opening in August 1959, a week before statehood, in the same year that jet travel began to the new state, that its developers began work on its planned second phase promptly after completion of Phase I, rather than five years later, as planned. Phase II opened in 1966.

The mall retained its original appearance for nearly two decades, while it consistently met and exceeded sales projections, proving itself a solid investment. But, by the early 1980s, ownership had changed, and the mall had new management. It was at this time that major updates and changes began. By the mid-1980s, coinciding with a boom in Japanese tourism and investment in Hawai‘i, Ala Moana drew about 40 million visitors a year, more even than Disneyland at the time. It was still just two levels. It had about 90-120 stores, many local ones that had opened at the mall in either Phase I or Phase II. The alterations in the 1980s started to move the mall away from what was envisioned in the 1950s, in the name of remaining “current.”

The first changes removed a significant portion of the center’s original art. A few years later the mall’s spatial arrangement was stratified. Higher-end shops were installed at mall-level, while mid-level and convenience-type stores were relegated to the dark, parking-lot-facing lower level. Shops that didn’t meet the management company’s expected production levels lost their leases altogether. In the late 1980s a third level was built along the central area of the mall – drastically altering the mall’s roof shape, along with the central courtyard/stage area, and adding about 70 tenant spaces. In this period, the mall’s management made the decision to focus on high-end retailers not readily available in Hawaii, shifting away from Lowell Dillingham’s vision of local shops filling most of the mall. In 1990, 12 new, high-fashion or accessories stores opened in the redeveloped central area, including Polo/Ralph Lauren and Chanel. Less than a decade later, Neiman Marcus opened a new three-story store on the ocean side of the center, above the food court. This new section of the mall was designed in a throwback to the Charles Dickey-esque architecture of Hawaii’s territorial period, very much in contrast to the original design of the center. Until 1999, when Neiman Marcus was complete, Ala Moana consisted of a single axis, and central courtyard, and retained most of its original plan and outer appearance. Neiman Marcus gave the mall a second axis, now like a short-legged T. A few years later, in 2006-2008, another new wing was added to accommodate another non-Hawaii-based retailer, Nordstrom. The wing contained space for fifteen new stores in addition to Nordstrom and expanded the mall’s total square footage to over 2 million square feet, three times its original size. Nordstrom’s design used some local material: coral-stone wainscoting, and planters filled with ti. But the reality was, the wing bore (and bears) a strong resemblance to “anytown outdoor/outlet mall, California USA.”

These days, Ala Moana Center has three to four levels, three sections along its length, and two separate cross-axes extending in different directions. For the most part, it looks like nothing so much as an open-air mall anywhere in the U.S. (with the weather to support such a thing. Many of its shops are outposts of one chain or another that can be found at other malls across the U.S. An exception is the international luxury brand shops, complete with suit-wearing greeters/bouncers at the doors that line the busiest mall areas. The lowest level hosts reasonably priced chains and occasional one-off local shops. The food court is also here, facing toward the ocean. These lowest-level shops all face parking, like a strip mall, but with an additional parking deck above. The coconut tree “pukas” that originally let sunlight through from above have become rare. Now, with added levels of parking above, light is scarce here. Most stores are located on the second level, where they face the interior passageways, open to the sky above. The third and fourth levels with mid-tier chain stores, and restaurants and bars, respectively, are located on the central and south-central portion of the mall and are also open to the central axis. Connections between these levels and axes are haphazard, and some have multiple access points, while others have few, or few that are readily found.

Most of the art is gone or hidden in the clutter of more and more stores and kiosks, none of the play areas remain, and none of the climbable sculptures. The basic structure of Phases I and II remain, but none of the decorative architectural elements are visible. The only parts of the original Ala Moana center that are still recognizable are the former Liberty House building, now Macy’s, and the Ala Moana Building, a high-rise medical office and banking annex to the mall, with its no-longer revolving restaurant space perched atop.

Even with all those changes, it is the most recent updates that have caused the greatest loss to what many of us remember as Ala Moana Center. These last two (or is it three) phases of construction were the demolition of the 1959 Sears building that had anchored the northern end of the center since forever; construction of (even more) parking, another department store –Bloomingdale’s, a residential tower, and a set of “ultra-luxury” condominiums facing the ocean.

Ala Moana’s nickname, or motto is “Hawaii’s Center.” And it truly felt like that for decades. It catered and appealed to local folks. At New Year and 4th of July the ocean-facing second level parking was full of folks in their cars to watch the fireworks shot from the beach park across Ala Moana Boulevard, and every Christmas season meant the appearance of the center’s “Big Santa” centered on the edge of that same parking deck. These touches, along with the design and retail mix of the mall made it feel like a comfortable part of the community. Even though folks were there to spend money, the center felt thoughtful. It was geared toward Hawaii’s everyday residents. Now, Neiman Marcus and the condos take up most of the space that had been that parking deck, and Santa is hardly visible next to the condos. The mall’s design and shops made it a destination for locals and visitors, which made it successful, which brought interest from luxury brands, which brought wealthier visitors/shoppers, which led to more and more construction. Now, people (who can afford it) can live in a luxury condo with a view of the ocean in what was Hawaii’s Center.

About the Author

Lesleigh Jones is the Secretary of the °®¶¹app/Hawaii board.

Sunny Spotlight: Modernism in Hawaii is part of the °®¶¹app Regional Spotlight on Modernism Series, which was launched to help you explore modern places throughout the country without leaving your home. Previous spotlights include Chicago, Mississippi, Midland, MI, Houston, Las Vegas, Colorado, Kansas, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, South Dakota, Vermont, and Albuquerque. View all Regional Spotlights here.

Have a region you'd like to see highlighted? Submit an article.

If you are enjoying this series, consider supporting °®¶¹app or so we can continue to bring you quality content and programming focused on modernism.