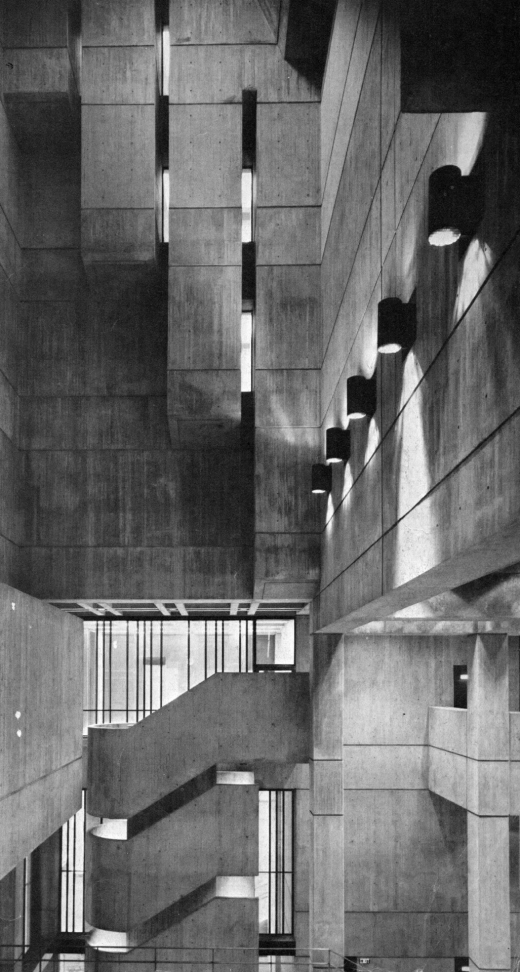

Edited version of comments presented on the occasion of °®¶¹app/New England’s annual meeting in the South Lobby of Boston City Hall, December 9, 2019.

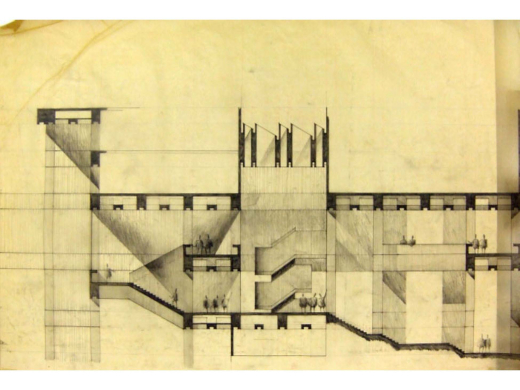

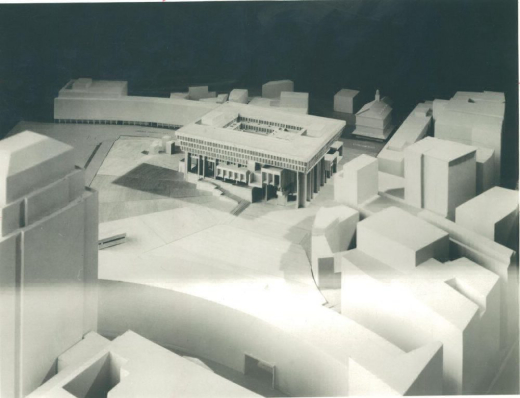

Being in the rejuvenated lobby of Boston City Hall for our annual meeting gives us the opportunity to reconsider briefly the story of the place, a half century after its opening. For those not familiar with it, this building resulted from an unusual nationwide design competition launched in 1961, a competition that drew 256 entries and that concluded with a distinguished jury unanimously selecting the design by a team of young New York architects, Kallmann, McKinnell and Knowles.

Those who are not aware of the immediate international impact of that competition design and of the building that followed may perhaps remember the response to a more recent legendary building, Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, of 1997. In an analogy I first made nearly 13 years ago when rallying people to support this then-threatened structure, Boston City Hall can be understood as “the Bilbao of its day.” Like that building, it was published seemingly everywhere, in both the popular and professional press; it attracted visitors from around the globe—including, in this case, members of the design professions who chose to relocate to Boston because the exciting building expressed a city’s innovative vision!—and it played a key role in stimulating, and representing, the city’s rebirth.