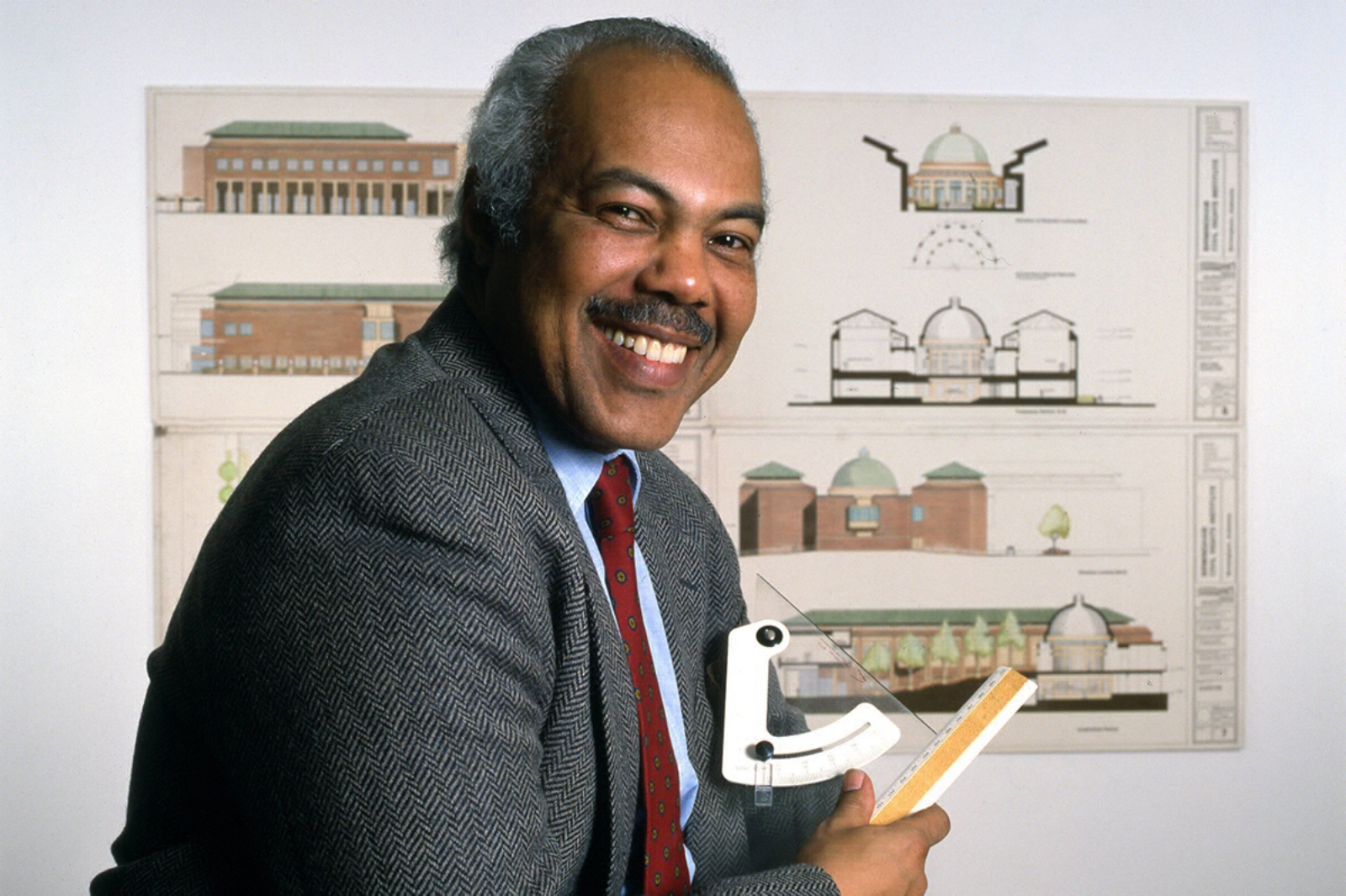

J. Max Bond, Jr.

Architect

1935(Birth)

18 February 2009(Death)

Biography

J. Max Bond Jr., (1935-2009) was born in Louisville, Kentucky to a distinguished Black family. His father was a prominent educator, his mother an accomplished civil rights leader, teacher and quilt maker. His uncle, Julian Bond, was active in civil rights, the Georgia state senate and was chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1988-2010.

Bond always says he was inspired to become an architect by a staircase that fascinated him at Tuskegee Institute and by architecture he saw in Tunisia as a boy, both places where his father taught. He enrolled at Harvard in the 1950’s where he was harassed for his race, and where a professor warned him against trying to become an architect due to the paucity of Blacks in the field. Fortunately, he persevered and went on to get a Masters in Architecture in 1958 and became one of the most prominent Black architects in the country.

That perseverance did not go unnoticed throughout his career. In his obituary for Bond in the New York Times, David Dunlap quotes Gordon J. Davis, the founding chairman of Jazz at Lincoln Center who said, Bond had a “steel spine and rock-hard determination – qualities always masked by a handsome gentlemanly exterior…”

Even with his family background and Harvard degrees. Bond did not find it easy to break into the profession of architecture. Initially, he left the States and went to France under a Fulbright apprentice under the direction of the French Modernist architect André Wogenscky (1916 - 2004). Afterwards, when he was unable to find work in the US, he found projects in Ghana. Eventually he returned and found work in the United States.

From 1967-68 he was head of the Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem (ARCH). And in 1970, Bond started his own firm, Bond Ryder & Associates with Donald P. Ryder. Some of Bond’s most notable projects were the Civil Rights Museum in Birmingham, the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Social Change and Memorial in Atlanta, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Studio Museum in Harlem.

When Ryder retired, Bond merged with another firm that became Davis, Brody, Bond. There, among other projects, he was partner in charge of the National September 11 Museum at the World Trade Center designed by architect Michael Arad. He also collaborated with David Adjaye on the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. There was always an unwritten law that Black architects did not get to work on projects below 110th Street. Bond broke that rule by working nationally and as far downtown as you could go.

Besides being an architect, Bond was a champion of young, Black architects and an educator. He was chairman of the architecture division at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture and Planning (1980–84) and he was dean of the School of Architecture and Environmental Studies at the City College of New York (1985–92). Bond was also a member of the New York City Planning Commission (1980–86).

The body of work Bond created and recognition he received, was a significant help to the community of Black architects. He once said, “Architecture inevitably involves all the larger issues of society….” His journey illustrates the hurdles Black architects have had to surmount.

-Compiled by Leslie Monsky, °®¶¹app/New York Tri-State

Sources: